“The painter should paint not only what he has in front of him, but also what he sees inside himself. If he sees nothing within, then he should stop painting what is in front of him.” - Caspar David Friedrich

|

| Ernest Hemingway |

Perhaps my reaction to his exploits is a bit heightened since I am Hemingway's opposite. I am not well-traveled, having restricted all of my American expeditions solely to our nation's northeast and only venturing to Europe a handful of times. I don't rush toward “the action”; I try to avoid it. In fact, I was much chagrined to find myself in Berlin a month before the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, when refugees were already streaming from Eastern Europe into Germany. The situation didn't excite me but instead made me feel rather imperiled. I prefer serene predictability to volatile stimulation and believe, for me at least, that quiet contemplation without intruding distractions is essential to artistic creation. So, as you can imagine, I've led a pretty narrow existence.

I've only set up permanent residence in a couple of locations, all within the borders of New York State. Moving definitely has many benefits. You get to explore new locations and discover new restaurants, stores, art centers, music venues and parks. It can be pretty exciting. On the other hand, the experience of moving can be extremely trying, making mundane tasks challenging and routine activities demanding. I would say that moving means exchanging the familiar for the unfamiliar.

My wife and I, along with our two young children, moved to our current location in the Hudson Valley nearly 30 years ago, and I can still remember the experience as though it were yesterday. We were thrilled and relieved to be exchanging our confined and impractical quarters in Brooklyn for a large house situated on about two acres of land in a semi-bucolic setting. In fact, our furniture and possessions which had crammed our railroad flat in the city barely filled our new space, leaving our new accommodations feeling sparsely furnished and almost unpopulated. During the first months in our new digs, I recall retreating in the evenings with my three-year-old son to an upstairs bedroom to watch the sole TV station we could access with our telescoping antenna, a local station that usually hosted college basketball games. Seated on a span of pristine carpeting in front of a portable TV set (the only object occupying the room), we gratefully watched grainy images of young sportsmen fading in and out of focus as they vied for athletic supremacy. We ate our meals at a folding table set up in our dining room. We had only one car, which meant that my wife was completely stranded at the house while I was at work; for entertainment, she would bundle up the kids, load them into a double stroller and head down the hill to visit a fenced-in cow sedately munching on greenery at the curbside. We were so navigationally challenged that every journey we made for any purpose whatsoever always had the same destination: the one major thoroughfare in the area with which we were familiar. Years later, we laughed at our foolishness, how we often traveled miles out of our way to visit a store or restaurant that had an equally appealing alternative just minutes from our home. Honestly, I could go on forever.

Even after our exodus from Brooklyn, my life continued to be anchored in New York City. I still worked full-time in Manhattan, and my daily commute stole four full hours from my day. Sometimes I felt how ridiculous it was for me even to return to the Hudson Valley each evening. Once home, I would grab a quick bite to eat, watch a bit of TV with my wife and head off to bed early, hoping to get something close to the minimal number of hours of sleep needed to preserve life. I didn't learn much about our home's surrounding area. Our new property was a place to escape to and decompress after a stressful week of work. I didn't make connections with our neighbors; I interacted with quite enough people at my office and didn't need to add superfluous folk to the mix.

My wife is a very different kind of person, extremely social and approachable. And let's not forget that she was marooned along with two toddlers at our home unless I and the critically important car were there – certainly a powerful incentive to get the hell out of the house and press the flesh. So she quickly made connections with our neighbors and a handful of local groups and organizations. At that time, most of what I learned about our new environs was gleaned from her casual interactions with a diverse assortment of helpful and knowledgeable townies.

I honestly can't remember who it was that first apprised my wife of a nearby park that would be just the right place for our little ones, but whoever it was certainly did us a great service. Prior to this, we had a rather limited selection of locations where we could go to visit a playground and perhaps take a walk in the woods. Tymor Park was the perfect setting for our young family. Located close-by in a bordering town, the park consisted of a cluster of structures and amenities: a stately, old house, barns, long outbuildings, equestrian facilities, tennis courts, baseball and soccer fields, stables, silos, a playground and a well-maintained swimming pool. Most importantly for me, there was a reasonably graded, unpaved hiking path, about two miles long and girding a sizable pond, that could be traversed by small children. This hiking path, which included a few inclined sections providing a mild cardiovascular workout, passed by an old boathouse and observation deck, the ruins of an iron furnace and a man-made waterfall. For years, we took advantage of the playground and the path around Furnace Pond, without realizing that the park was actually much larger than we had believed it to be. We later discovered that, on the outskirts of the park, across some active roadways, are acres and acres of woodlands offering secluded and challenging hikes up and along a ridge of hills. In fact, encompassing over 500 acres, Tymor is the largest municipal park in New York State. We became aware of these additional holdings just as our boys were growing older and serious exertion became more inviting than swinging on a swing or shooting down a slide. In the right weather during certain seasons, the woods could assert a spooky aura which I, being an impish parent, would play upon to give the kids a thrill – hopefully not so intense as to keep them up at night or turn them off to hiking altogether. Generally, our travels were uneventful, lyrical and exhilarating. The trails in the deep woods are rarely used, and I've only come across a fellow hiker out there a handful of times in literally decades of visiting the park. These days, with the kids all grown, I hike alone and almost always opt for the secluded, outlying trails through the hilly backwoods. It's truly a joy to escape the frenetic demands of contemporary living and experience an hour or more of peace and isolation in a scenic, natural setting.

|

| Mark Twain |

Within just the last year, I learned that the park has an interesting history. This is going to get convoluted, so bear with me. In 1884, Samuel Clemens, known to most by his pen name Mark Twain, frustrated with his publisher, decided he would open his own publishing house and appointed his current agent, Charles Webster, as its director. Twain had reason to have every confidence in Webster. Beside serving as his agent, Webster had married Twain's niece, Annie Moffett, in 1875. Initially, Twain's publishing house was a success, but within less than a decade sales had fallen off precipitously. Webster, stressed-out and overworked, suffered a nervous breakdown, and Twain fired him. Sadly, Webster committed suicide in 1891. But during their marriage, Webster and Annie Moffett (who incidentally lived until 1950) had three children, and their only daughter, Jean, studied at Vassar College, traveled the world extensively, advocated for impoverished children and women's suffrage and became a successful and well-known author. In fact, one of Jean's books, Daddy Long Legs, was adapted into a popular play and later made into a movie which starred Fred Astaire and Leslie Caron. Jean eventually married Glenn Mckinney of Tymor Farms in Union Vale, Dutchess County. (“At last, a connection to Tymor Park!”, you exclaim.) Glenn and author Jean lived in marital bliss on the farm until Jean died after giving birth to a daughter at Manhattan's Sloan Hospital for Women in 1916. The child, also named Jean, survived and years later went on to marry Ralph Connor, the couple choosing to continue living at Tymor Farms. In 1971, Jean and Ralph donated the farm to the Town of Union Vale to be used as a public park. Six years later, the couple turned over to Vassar College 52 boxes of material that had been stored in barns and attics on the farm for decades. This material consisted of manuscripts, letters, notebooks, scrapbooks, journals, clippings and photographs gathered by several generations of family members who had lived at the farm and included among it was a large number of public and personal documents of Mark Twain, many of which scholars had no idea existed. I had been visiting this park for close to thirty years and had no knowledge of its history. I was particularly blown away to learn of its connection to Twain, a preeminent American author whose writings I had studied extensively while in college and continued to research after graduation. By the way, of Twain's four children, three died tragically before his own death, and his sole grandchild passed away without having any children of her own. This may explain how many of his belongings ended up in his niece's possession.

|

| Tymor Plaque in Recognition of the Connors |

During our nearly three decades of living in the Hudson Valley, we've learned of many amazing parks located quite close to our home. Each of them offers a few unique features such as challenging climbs, amazing views from great heights, extensive trails, scenic lakes and ponds, rushing waterways, roaring waterfalls, open fields, rock scrambling, historic buildings and ruins, fire towers, ice caves, flower gardens and abandoned orchards. I have visited many of these nearby parks multiple times and must observe that some of these features I've listed are not available at Tymor and those features that are available there are often exceeded by far in quality at other locations. For instance, the scenic views at Minnewaska Park or Schunemunk Mountain cannot be rivaled by those from the wooded hills of Tymor. The climb to the top of Bear Mountain is far more formidable than anything Tymor can offer. The deteriorating wooden structures at Tymor cannot compare with the mansions and gardens of the Roosevelt and Vanderbilt estates. All true. But Tymor offers probably one of the widest variety of these features among all our nearby parks and, for the most part, the quality of these features is of a truly praiseworthy character. I don't want to wax so poetic here as to lose all credibility, but I'm going to try to explain to some degree why I've formed such a strong attachment to this location. The park is pretty isolated, even the drive to it providing gorgeous views of open landscape, an ancient graveyard, rolling hills, horse farms and wooded avenues. It is nestled on all sides by ridges of hills that, depending on the time of day and the season, turn golden red or rust or grayish purple or deep green or cobalt blue. And being isolated, the park is not overrun with hordes of visitors. In fact, on most days my little Mitsubishi Mirage will share the large unpaved, dirt parking lot with only a few other cars. On the modern playground, you might find a couple of parents overseeing their children at play, but the trails are usually unoccupied. You're able to meander through this beautiful place free from distractions or interruption solely immersed in your private thoughts. Often the sound of trickling rivulets or rushing streams or crashing waterfalls accompanies your travels. There is a truly timeless quality to this park. While hiking you come across evidence of the endeavors of previous generations: century-old clapboard houses, farm structures, abandoned recreational facilities and the ruins of industrial works established in the early 1800's. Some of the hiking trails bear Native American names like Teaghpacksinck and Foghpacksinck. Would I be going too far to suggest that the park asserts to each visitor that he or she is part of a continuum, that their momentary experience of this place is not unique or individual but simply a facet of an endless communal connection with this land?

Many times while roving within the confines of this park, I am struck by the beauty of the scenery. Often the view of a wide expanse or even a seemingly insignificant detail will inspire within me a powerful emotional response. I can't explain this, but locations within this park frequently provide the quintessential, picture-postcard representation which defines for me the best of what each season affords. So, naturally, I've taken literally hundreds and hundreds of photographs at Tymor. Many of my photos document the same location, even the exact same perspective, but, for me at least, each is specific, asserting a unique character and mood. I will provide here a small selection of the vast number of photographs I've taken at this park over the years. Some of these pictures are actually scanned images from early film prints, so the quality of this selection may vary some.

We've even twice used the park as a backdrop for our annual Christmas card photo.

It occurred to me recently that I've probably painted the scenery at Tymor more often than at any other location. I don't commonly paint landscapes. It's not that I disparage the genre. In truth, I find the landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich, Ferdinand Hodler, Vincent van Gogh, Fairfield Porter, Richard Diebenkorn, Andrew Wyeth and Anselm Kiefer (to name just a few) to be truly stirring and effectively expressive of a distinct emotional state. But I struggle with landscape. For me, it's a matter of focus. In painting a landscape, I have trouble determining where to direct my energies and end up with an overall unsatisfactory execution. I think I get impatient and lazy. The figure remains for me my most natural instrument of expression. But I do paint scenes from nature now and then, especially while on vacation at a particularly impressive locale. And since retiring, I now have more frequent opportunities to explore local parks and trails, which regularly spark an interest in documenting a scenic vista. All the same, I still very rarely tackle a landscape and even more rarely will I approach a landscape as a weighty, laborious effort. I would define most of my landscapes as “studies”. This is why I was surprised to recognize recently that several of my major works have been inspired by the scenery at Tymor.

In 2003, I created View from Tymor, a large oil painting executed on canvas, which documents a view from an elevation overseeing roadways crisscrossing the park, bordering trees, scattered structures and distant fields and hills. I thought of this work as an abstract “symphony” composed of various movements whose details could be reorganized, emphasized and distorted in acquiescence to the whole.

|

| Gerard Wickham, View from Tymor, Oil on Canvas, 2003, 46" X 52" |

The following year, I painted on a wood panel Furnace Pond, Tymor Park. There used to be a deck above Furnace Pond at which my wife and I would occasionally set out on a picnic table a huge spread of cheeses, meats and other delicacies for our children to enjoy while we shared a bottle of white wine. I was decidedly interested in how the bright spring sunshine would wash out the tonalities of the distant pond, fields and hills leaving only the deck and the curtain of trees immediately behind it richly colored and in focus. It was an effect that definitely struck an emotional chord within me, and I set out to capture it in paints.

|

| Gerard Wickham, Furnace Pond, Tymor Park, Oil on Wood Panel, 2004, 17.25" X 22.5" |

In 2018, the first year of my retirement, I decided that once the weather was reasonably mild I would get outdoors regularly to record some of the local scenery. Most of these works were not very accomplished, but I was happy with a few of them. Tymor in Autumn, a detailed portrayal in gouache of an old clapboard house on the outskirts of the park, was one of the last landscapes that I produced that year and is, in all likelihood, my most successful effort.

|

| Gerard Wickham, Tymor in Autumn, Gouache on Paper, 2018, 14" X 9" |

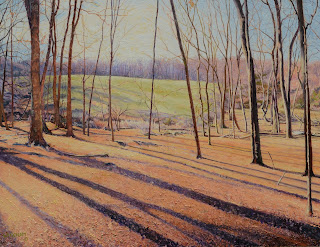

With the COVID pandemic raging in 2020, I believed it would be irresponsible to organize a multi-figure modeling shoot in preparation for a major work and instead began to entertain thoughts of executing a large landscape painting. In the autumn of that year, many months after the initial outbreak, I was hiking alone in the backwoods of Tymor when inspiration struck. During that first year, I probably did more hiking than I had ever done before in my entire life. On that particular afternoon, I chose a trail that would take me directly to the top of a long ridge of hills. This route ran parallel to a small stream confined within a rocky chasm situated between two wooded slopes. As I achieved the summit, the trail abandoned the stream and headed straight into the woods. A few minutes later, I looked off to my left and saw a scene that probably wouldn't excite the interest of most hikers but really grabbed me. It was late November and the trees were already bare, their discarded leaves several inches deep on the forest floor. Beyond the trees was, inexplicably, an open field, still green with life, and behind that field was a thick screen of violet-gray trees, barely permeated by sunlight. At that time of year, the days are really short, and the sunlight seemed weak and impotent to me. Even though I had gotten out pretty early that afternoon, already the day was waning, the low sun casting lengthy shadows across the fallen leaves. The scene was so melancholy, so emblematic of the end of the bountiful growing season and so filled with foreboding of the bleak winter to come that I stopped in my tracks momentarily steeped in sorrow. Everything about me at that moment seemed absolutely tenuous, vulnerable and transitory. I know this sounds ridiculously melodramatic, but I thought about the changing of the seasons, how the cycle of the seasons related to the cycle of life, which in turn evoked a cognizance of the inevitability of physical decline and ultimately death. The scene before me palpably elicited such thinking. Luckily I had taken my camera with me that afternoon, so I was able to take a series of shots of the scene. It actually took me several days to grasp that this scene would be the subject of my next major work.

After preparing my canvas, I set to work with some loose concepts in mind. Initially, I felt that I might approach this landscape in a Cézannesque fashion, not apishly imitative but vaguely accepting of a fragmentation of form – an effect suggested by the weak autumnal light filtered through a prism of bare tree limbs. I actually devoted several sessions to this approach before recognizing that it wasn't legitimate for me, that I was adopting an artificial vocabulary not true to me. I briefly considered employing a very heightened palette of impasto brushwork, something akin to the technique employed within the compositions of Wolf Kahn, but again this approach was rejected as “dishonest”. At that point, I decided to let my image evolve organically. Though light was very critical to this work, I didn't want the painting to become too atmospheric; my trees had to be solid, weighty forms which spanned the gulf between foreground and sky. I felt strongly that I didn't want this painting to become “fussy”, a direction my natural tendencies veer toward, so I forced myself consistently to use brushes coarser and larger than would seem appropriate to my immediate needs. I wanted my paint handling to be crude and essential. I wanted to minimize technical affect. I was seeking candor.

It took me a full year to complete this landscape. To be honest, I must confess that I wasn't working too diligently and consistently on it. Perhaps experiencing the pandemic stripped me of some focus. For a good chunk of the first phase of the COVID-19 lockdown, our home was filled to the rafters with a crowd of idle workers, a student on hiatus from studying and retired me, and all that inactivity led to some excessive partying. However, if I truly make an unbiased evaluation of my behavior at that time, I would conclude that I was simply not motivated. This landscape provided a distraction for me. When I opted to go up to my studio, I really enjoyed the effort of painting, was satisfied with the approach I had chosen and relished the level of concentration I achieved. But then days would pass without my crossing the threshold of my studio. I have no regrets. It was just what had to be.

When I finished this painting late in 2021, I left it sitting on my easel for weeks and would occasionally visit it to consider the result of my endeavors. Let me make clear that this landscape was not intended to be an austere momento mori. Of course, as stated earlier, I wanted to capture a specific light and a specific mood that late autumn asserts, but, for all its focus on endings, the painting is pretty colorful and vibrant. I particularly enjoy the proximity of zones of orange, green and purple, an aberrant combination for me. Regardless of my response to its coloration, this painting disconcerted me. It is not edgy or outrageous or provocative; it is purposeful and raw and unsophisticated; and I wondered if viewing it offered any recompense... if aesthetically it could please or excite or offend... if it communicated any of the emotional content which I intended. For quite a while I was undecided. It wasn't until I hung the painting on a wall which I pass multiple times on a daily basis that I was able to reconcile myself with this work. I'm satisfied with it.

|

| Gerard Wickham, Deep Woods, Tymor, Oil on Canvas, 2021, 34" X 44" |

As I am finishing up this blog entry, it now occurs to me that I may have done a horrible thing. I've let the proverbial cat out of the bag. In singing the praises of this secluded, little-known spot, I could be compromising the very attributes that please me most about Tymor: its serenity, tranquility and lack of crowds. I can envision vying for a parking space in the unpaved lot, waiting in a long line at Furnace Pond's waterfall to catch a glimpse of its sonorous effluence and being accosted by hordes of fellow hikers on remote trails in Tymor's forests. It's a pretty grim prospect. Then I recall that my blog enjoys only a very minuscule following making my fears completely unfounded. I can let out a sigh of relief. And to that small assortment of crackpots and eccentrics who actually read my blog, I hereby announce that I gladly invite you to come and experience this wonderful location. Perhaps I just might run into you on the dirt paths tracing the hilltops above the park. We could share a granola bar, hike a few miles together and enjoy a long talk about art.

As always, I encourage readers to comment here. If you would prefer to comment privately, you can email me at gerardwickham@gmail.com.