This

entry will be different. It's not going to be about Art, as nearly

all of my entries are. It will be about a simple lantern.

In late

May, one of my sons was returning from a trip to the Midwest, and,

anticipating a drive of over a dozen hours, he would not reach our

home until nearly midnight. All of the family waited up for his

arrival, knowing that he would have some interesting stories to tell

of his travels. But we had a problem. My son had been out in the

big world, eating at restaurants, stopping at rest areas and mixing

with a fair number of people. It was possible that he had been

exposed to COVID-19, and, at our home, we had been following strictly

the suggested guidelines for stopping the spread of the virus since

late March. He would have to be isolated. My wife and I set up a

living space for him, providing a bed and a few pieces of furniture

and preparing a work area where he could write, use his computer and

eat his meals. I purchased a large tarp and hung it across the

entrance way to his new quarters, and I placed a tiny 5 inch tall

Baby Yoda that my wife had crocheted on the desk to keep him company.

But we still hadn't resolved the problem of how the family would

gather with him upon his arrival.

|

| Baby Yoda |

It

seemed to me that the only safe way for us to share a common space

would be if we met outdoors in our yard and practiced social

distancing. Being May, the nights were still pretty cool, but a

sweatshirt and a pair of long pants would be sufficient to ward off

the cold. I pulled six chairs out of the garage and organized them

so no one would be closer than six feet from our sequestered

traveler. Turns out it was a moonless night, making it nearly

impossible for me to see what I was doing out in the garage. I was

stumbling over garden hoses, paint cans, a few discarded two by four

studs, bags of potting soil, chicken wire fencing and a remote

control vehicle – a vestige of our children's early years. I

should mention that our garage is situated at the top of our

property, separated from our home by about fifty yards, and has no

electricity. The night was so dark that I thought it would be a good

idea to provide some kind of lighting – just to make sure we didn't

break our necks. My first thought was to bring out a couple of

candles from the house, but the night was too breezy; they wouldn't

stay lit ten minutes. Then I remembered an old lantern that would be

perfect for shielding a candle from the wind – if only I could find

it. I returned to the house and, to my surprise, after just a few

minutes searching, found the desired item. I grabbed a stub of a

candle left over from some family gathering and headed back up the

property. Once the candle was lit, everything was set for my son's

arrival. My wife joined me in the yard to have a beer while we

waited. According to our estimations, my son was expected home

within the hour, and we wanted to be sure to intercept him in our

driveway before he might inadvertently rush into the house thereby

potentially contaminating our living space.

These

are strange times indeed.

|

| Petrus van Schendel |

As we

quietly talked, I glanced over at the lantern sitting on our picnic

table about ten feet away. I had left its small doorway open to

provide more light, and the candle's flame danced in the wind's

gentle currents. Surprised at how much light a single candle could

provide, I focused on the flame, then examined the intricate

patterning that had been cut into the lantern's shell. It occurred

to me that this dusty, old lantern and I shared a history going back

about forty years, and, as I often do these days, I started to

reminisce.

My Aunt

Lillian, my father's sister, was 30 years old when I was born, which

meant that she was about a decade younger than my parents and most of

my aunts and uncles. She was different than they were. They had

grown up during the Depression. The men had fought in World War II.

And by 1959, the year I was born, the men were solidly settled in

careers and the women, even those with careers of their own, had

already given birth to most, if not all, of the children they would

have. My parents and my aunts and uncles were “adults”. I guess

at some point in the distant past they had sown their wild oats but

by that time had matured, put on a few pounds, accepted the routine

and responsibility that comes with having a family and didn't have a

lot of interest in frivolous things. But, like I have said, Aunt

Lillian was different.

Aunt

Lillian was contemporary. She dressed stylishly. Her wardrobe was

colorful and patterned a wee bit dynamically as was the mode in the

1960's. On occasion, she even wore jeans – something still

controversial for adult women at that time. She was slim and

youthful. She wore her hair in a tasteful, impeccably maintained

bouffant, which was covered in a fashionable headscarf when outdoors.

She was chic in an Audrey Hepburn – Breakfast

at Tiffany's sort of way.

|

| Aunt Lillian with me and my sister |

Aunt

Lillian never married, so she would often visit with her siblings'

families whenever the opportunity arose. She would stay with us for

the entire weekend, and, long after my father had gone to bed on a

Saturday night, my mother and aunt would stay up smoking cigarettes,

drinking beer and having private conversations that we children were

not privy to. During one of her visits, she brought my brothers,

sister and me to the beach, and we pulled her fully dressed into the

surf. She just laughed. Because she was freer than most of the

adults I knew, she was able to travel, making multiple trips to

Europe and elsewhere over the years. I recall that once she flew to

Ireland to visit family there and spent a number of days sightseeing

in the countryside in a gypsy caravan. In her bedroom, there was a

dish that held all kinds of exotic coinage, loose change collected

over years of travel; at our home, only the occasional maple leaf

emblazoned Canadian penny cropped up. Aunt Lillian introduced me to

fondue, caviar and good wines, and she listened to classical music.

She took my sister with her to see Doctor

Zhivago at our local movie

theater. Aunt Lillian was different.

She

attended birthday parties, baptism, communion and confirmation

celebrations, graduation ceremonies, showers and weddings. When I

had a solo art show at SUNY Stony Brook, she drove from Rye, NY to my

school, a considerable journey, especially after a full day's work,

to attend the opening. But Aunt Lillian had a unique role to play.

Being unmarried and childless, all of her nieces and nephews were her

children too, and she did her damnedest to support us in all our

multifarious endeavors. In later years, Aunt Lillian, a free spirit

during my early childhood, didn't adjust easily to the changes that

were occurring in American society in the late 60's and 70's. They

were radical times in our nation's history with countless “movements”

continuously cropping up that challenged our perceptions and values.

Our society was fracturing, not into a multitude of narcissistic

fragments but into two camps: the old and the young, and that breach

was achieved in a riotous, contentious upheaval. If you were the

parent of children coming of age during this period, you were forced

to evolve, to some degree, with them. You would be introduced to new

ideas and ethics. You would be indoctrinated into the new code of

informality. My parents, like most during those days, made the

transition in a herky-jerky fashion, sticking to many of their core

values while accepting that society was changing and recognizing

that, if they were going to maintain a functioning relationship with

their children, they had to tolerate our distasteful customs and

attitudes. By the time I started college, my parents had been “worn

down” from countless, minor insurrections and a fairly congenial

truce had been effected. Aunt Lillian didn't have children to usher

her into this new era, and she retained many of her beliefs and

habits in spite of the changes that were going on around her. She

appeared a bit reactionary, somewhat Victorian. We would have silly

arguments about the environment, the sexual revolution, the new

openness. Occasionally, she would critique us children, evaluating

our activities or choices from a perspective that seemed absolutely

antediluvian. I recall her informing me when I referred to my mother

as “she” that “she” was the cat's mother. I was bewildered.

“But Aunt Lillian,” I protested, “it's just a pronoun.”

|

| Aunt Lillian (l.) and Aunt Mary |

But, in

truth, we negotiated those days without an inordinate number of

collisions and clashes, and, even during my college years, I would

accompany my family on visits to Aunt Lillian's apartment in Rye. It

was during one of those visits that I noticed as we were preparing to

head home two lanterns sitting atop opposite ends of the shelving

that spanned one wall of her apartment. They were simple lanterns

constructed of panels of blackened tin pierced in patterns of dots

and dashes. The cone of each lantern was capped with a circular

grip, and a hinged doorway permitted access to its interior. They

looked primitive and excited my interest, which was particularly

strong at that time, in everything “old”. (I carved Viking

styled figures and patterning in wooden beams, brewed homemade mead

in my mother's kitchen and made paintings and drawings paying homage

to Woden and Llyr. My area of focus for my English degree was Middle

English Literature, and I ravenously read Chaucer, Viking sagas and

Middle English lays, lyrics and romances. Jethro Tull's Songs

from the Wood was my

favorite album in those days.) So I stopped to admire the lanterns.

Aunt Lillian explained that she had purchased the lanterns from one

of my cousins who was selling them as part of a fundraising effort

for some worthy institution. If I recall correctly, she said my

cousin had actually participated in the construction of them. I

guess I raved about them a little too enthusiastically because Aunt

Lillian reached up, removed one of the lanterns from the shelf and

handed it to me. I was mortified. “No, Aunt Lillian,” I argued,

“I didn't mean to...I don't want to take your lantern. I mean I

appreciate it, but I can't.” She just laughed and said, “One

lantern is enough for me. Really. Hope you enjoy it.”

And

that's how I came into possession of the lantern that I went in

search of the night my son was returning from his journey.

|

| The Actual Lantern |

Immediately,

the lantern found a critical function. The house I grew up in was a

rather compact ranch with kitchen, living room and dining room

clustered tightly around a central stairway that led to the basement.

There was absolutely nowhere private to congregate if my friends

stopped by to visit. We would gather at our kitchen table, the sound

of the blasting television howling in the room and, every so often,

my father angrily demanding from the living room sofa that we “keep

it down out there!” So if the weather was in any way tolerable, we

would retreat to the yard to share a couple of beers and shoot the

bull. There was an outdoor light installed above our backdoor, but

we would prefer to sit in darkness rather than be vexed by its

blinding glare. Once I got the lantern, it became our regular

companion during our gatherings. In the midst of my thoroughly

suburban neighborhood, I enjoyed seeing my friends' faces lustrous in

the golden glow of a flickering candle and imagining, however feebly,

that we were creatures of a different age – simpler, more primitive

and more essential.

|

| Jan Steen |

It was

about this time that my friend Tom suggested that we attend a lecture

on Transcendental Meditation that was to be given at our local

library. I had known Tom since we met in Junior High School. He was

in most of my classes and was part of the regular crew who occupied

the same table in the lunchroom each day. Though we remained friends

in High School, we didn't see quite as much of each other because

there were now two “accelerated” classes and they were

essentially divided between band and non-band members. My musical

career had ended with my graduation from elementary school; Tom

played bass guitar and was in the school band. All the same our

paths still crossed several times each day, and, of course, we

regularly got together with a core group of friends outside of

school. I thought moving on to college would mean the end of our

relationship, more or less, but I was shocked to run into Tom at my

orientation session at SUNY Stony Brook in the summer of 1977. He

was never in any of my classes, but we met up for lunch most days and

ran into each other on campus fairly often. It was fantastic to have

a close friend around, especially during my first year of college

when I was adjusting to this new environment and new

responsibilities. Tom was studying journalism, and I was striving to

secure two degrees in English and Studio Art. Tom was very

open-minded and curious, driven to meet new people and explore new

situations. I was a cynic, suspicious of people's motives and

resistant to new ideas. I considered myself a realist. In fact,

another friend and I were engaged in a series of conversations,

sparked by our reading of Tolstoy, in which we concluded that only

through cool, dispassionate, intellectual evaluation could one hope

to come to a full understanding of anything. Tom jumped into things

full throttle, while I cautiously dipped my toe in to test the

waters.

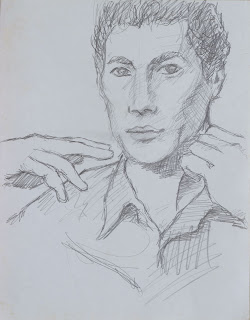

|

| Sketch of Tom - c1980 |

So when

Tom proposed that we should attend this lecture on Transcendental

Meditation at the library, I was less than enthusiastic. “It's

just going to be a sales pitch,” I objected. “But it should be

interesting,” he responded. “I really doubt it,” I replied.

“Come on! What can it hurt?” “Aw!” I moaned. I ended up

attending the lecture with Tom more out of friendship than scholarly

curiosity.

The

lecture had yielded what I thought was a pretty good turnout of local

residents willing to devote an evening to learning about a relatively

new discipline brought to the US from India. The speaker took the

podium and addressed the audience. I felt his talk was very

pragmatic, not the murky mysticism I was expecting. He explained

that Transcendental Meditation was simply a means of dispelling

distractions, achieving a thoroughly relaxed state and attaining an

enhanced ability to concentrate. Two short sessions of TM per day

offered a multitude of benefits. Practitioners would feel better

rested and more energetic while requiring fewer hours of sleep each

night. In addition, TM could induce a greater sense of contentment

and inspire creativity. He also talked about health benefits, in

particular the potential to ameliorate the symptoms of hypertension.

And, as a college student, I was especially excited by the claim

that, by acquiring the ability to block out distractions and improve

focus, my studies would be made easier and I would absorb material

more readily. He explained that if one continued with the program he

or she would be assigned a mantra, a personal Sanskrit word or

phrase, that would be silently repeated by the practitioner to assist

in emptying the mind of all thought and bring on a state of utter

relaxation. The mantra was unique to the individual and should never

be revealed to anyone else. Of course, the thrust of the lecture was

to sign up participants for a multi-step program which involved a fee

structure that far exceeded the means of a financially strapped

college student, but I wasn't turned off by the presentation. On the

contrary, it actually intrigued me. The speaker ended his lecture by

teaching us an exercise that we could all easily perform without

further instruction, which involved staring at the flame of a candle

until its image became established on our retinas. We were to close

our eyes, then attempt to retain and stabilize the afterimage of the

flame for as long as possible. With practice, our ability to control

the afterimage would strengthen, and, hopefully, in the process, we

would actually initiate our first experiences of meditation.

Returning

home that night, I thought I would give the flame experiment a try.

I was living in my parents' basement at the time, so I could explore

this technique in privacy and without disturbing anyone else. I

placed the tin lantern on the table beside my bed, lit its candle and

turned off all the lights. After focusing on the flame for quite a

while, I closed my eyes and, sure enough, its afterimage appeared

quite distinctly on my retina. The flame drifted slowly to the

right, and when I attempted to bring it back to center, it darted

about wildly, veering out of my field of vision entirely. I managed

to recapture the image of the flame only to watch it fade rapidly

into the darkness. “No problem,” I thought, “The instructor

said that this skill would take some time to master. Rome wasn't

built in a day.” I performed this experiment several more times

that night achieving similar results before pulling up my blankets

and going to sleep.

|

| Georges de La Tour |

The

flame experiment became part of my nightly ritual. After my reading,

I would light the candle in the lantern, shut off the lights and

practice my rudimentary TM technique. I might perform this exercise

three or four times each night. The routine wasn't difficult or

unpleasant, so committing to this activity didn't represent a

hardship. But despite many months of performing this exercise, I

must admit that I saw absolutely no progress. I was neither more

successful at controlling the movement of the afterimage nor better

able to retain the image longer. I chalked this failure up to my own

deficiencies, my dependence on a Western way of addressing perception

that advocated logic and analytical discourse as the best means to

achieving enlightenment. My mind was unable to relinquish active

thought. Recognizing this, I called an end to the flame experiment

and chose instead to listen to classical music as I fell asleep.

I still

continued to use the tin lantern to light my nighttime gatherings,

and it followed me to each of my three apartments in Brooklyn and

then up to Dutchess County. When my kids were small, I was more

likely than now to pull out the lantern to lend a little romantic

ambiance to an evening's activities in the yard, but I've never

abandoned it completely. Over the years, an amalgam of many

different colored waxes has accumulated in its bottom and a coat of

dust has collected on its shell. I tell myself from time to time

that I should rehabilitate the old lantern, but never seem to get to

it. It remains on display on the stone ledge that skirts the base of

our living room's fireplace where it occasionally asserts its

presence and its history on my consciousness.

And

here's my point. If you're around long enough, it's more than likely

that your home will inadvertently become a museum housing the

detritus collected over decades and decades of living. Honestly, I

can just quickly glance around in any room of our home and find a

multitude of items that unearth a host of memories. On our bookshelf

perches the small teddy bear, a little worse for wear, that was my

companion when I was just a baby. The low, wide chair that my

siblings and I bought for our grandmother many years ago sits in my

living room, even its reupholstered

epidermis now frayed after repeated onslaughts from our cats.

(Incidentally, this low chair still proved insufficient to meet my

grandmother's needs, and she was provided with a stool on which she

could rest her feet when seated there.) Displayed above it is a

flask I purchased in Germany thirty years ago so I could enjoy an

occasional nip while hiking in the Bavarian Alps during a rather cool

October. In my closet, hangs the corduroy jacket I bought for my

first real job interview – I wonder if it still fits. As I type

these words, a wooden rocking horse that my wife and I bought in

Brooklyn as a Christmas gift for our oldest son peers out at me from

our front door's vestibule. A decade later, I spent my evenings

restoring this rocking horse, after years of abuse from three raucous

boys, in expectation of the imminent arrival of our fourth child –

who, by the way, is now eighteen years old. Truly, I could go on

listing similar items endlessly. It's kind of reassuring to be

surrounded by these things; they remind me that we're all part of a

continuum, that our imprint on this planet is not completely

ephemeral. However I also recognize that sometime soon after I'm

gone these accumulated “souvenirs” will lose their magic and

become simply objects once more.

|

| Godfried Schalcken |

I

believe this entry must conclude with a few followups to some of the

stories I touched upon within it.

My son

remained asymptomatic throughout his isolation, and, after his two

week quarantine, he rejoined the rest of the family living in our

home. I was pleased to note that he handled his period of

confinement with relative ease, maintaining for the most part an

upbeat attitude while enduring his life behind a plastic tarp.

My fiend

Tom married and moved to Maine where he and his wife raised their

family. He did become a successful reporter and currently writes for

an organization committed to preserving island and coastal life in

Maine while promoting a healthy environment. It's hard for me to

fathom, but Tom is now a grandfather.

When my

wife and I bought our home north of the city, I immediately thought

about inviting Aunt Lillian up to spend a weekend with us. The

purchase had left us strapped for cash, and we were furnishing the

house piecemeal, buying things here and there as our budget

permitted. For instance, we ate at a folding table for what seemed

an eternity before finally securing a dining room set. I didn't want

to have my aunt up until we could entertain her... well not properly

(that was definitely beyond our reach) but maybe passably.

Unfortunately before we could get our act together, I received word

that Aunt Lillian was seriously ill. She passed away at the age of

sixty five a quarter century ago.

Though

my foray into Transcendental Meditation didn't go well, I maintained

a curiosity about Eastern doctrines. During my undergraduate

studies, I enrolled in a course on Indian Philosophy in which we read

selections from the Bhagavad Gītā,

the Ŗg Veda and the Upanișads. The material proved to be too

esoteric for me, and I really didn't get much out of the class.

Later in Grad School, I took a course on Chinese and Japanese Art

that sparked a lasting interest in Zen Buddhism. On my own, I began

researching this philosophy which complimented my fixation at that

time on the writings of Yasunarί Kawabata and Yukio Mishima.

Though I remain steadfastly irreligious, Zen Buddhism appealed to me

as the most practical and applicable of the world religions with

which I've become familiar. The concept of Yin and Yang definitely

contributed toward my artistic development, particularly my

fascination with duality and contradiction. For the last thirty

years, a jade Buddha pendant has hung from my neck not to proclaim my

adherence to a religious doctrine but to express my dissatisfaction

with all absolutes and emphasize my conviction that, regardless of

how comforting it is to assess people and events in tones of black

and white, any significant perception of experience must recognize

that everything is painted in shades of gray.

As

always, I encourage my readers to comment here, but, if anyone

prefers to respond privately, I can be contacted at

gerardwickham@gmail.com.