“There’s no retirement for

an artist, it’s your way of living so there’s no end to it.”

- Henry Moore

So, as previously stated,

one of my retirement goals is to become proficient in the use of gouache, an

opaque medium similar to watercolor.

There are a couple of advantages to gouache. You can thin it with water, so there are no

solvent fumes with which to deal. It’s very portable making it ideal for

painting on location. Your brushes and

palette can be cleaned with soap and water.

And, most important for me, because of its opacity, you can rework areas

and cover up mistakes, a critical feature for me since I tend to rely on the

“trial and error” method often in making determinations while painting. One reason I’ve struggled with watercolor in

the past is its transparency makes recovering from my “experimental excursions”

impossible.

I’m pretty sure that I had

two tubes of gouache in my pencil box at one time. I never explored their potential seriously,

using them more as an occasional supplement to enhance my graphic work. But I am ready to roll up my sleeves and

master their use now. At this point in

my life, I am basically an oil painter who spends months on a single work,

building up layers of paint to arrive at the exact tones and textures I

desire. Yes, I’ve become a bit slow and

fussy, not a horrible thing but not a great one either. I thought it might be a good experience for

me to tackle a new medium, one that might encourage me to be a little more

spontaneous and inventive. After all,

gouache paints and decent watercolor paper are relatively cheap, and there’s

really no preparation involved. So I can

certainly shrug off disappointing results gracefully, abandoning an unpromising

effort in its embryonic stage rather than toiling stubbornly to save the work.

These days, whenever I want

to learn a new technique, I turn to the internet. There I can usually find an endless array of

videos available providing instruction and demonstrations. These videos are really a wonderful resource,

the only problem being that often the quality of the material can be poor or

designed for a lay audience. Some of the

gouache demonstrations were clearly intended for craft enthusiasts, but I did

find a good many that provided professional instruction for artists. From these I got the impression that gouache

could be used very much like oil paint, applied in thick, lush strokes and

built up in layers. This appealed to me

very much, and I was eager to start my first project.

I already knew that I would

work on a series of self-portraits. I

wanted to work freely from a live model, and I recognized that I was the only

model available who was willing to pose for hours at a time, sometimes for

several consecutive days. Another

benefit of using me as my subject matter was that I didn’t have to flatter or

satisfy myself. I could experiment with

this new medium without constraint, portray myself unconventionally, strike unusual

poses and produce unquestionable failures, and I would be fine with that. I couldn’t imagine a volunteer model being as

understanding.

Another predetermination I

had conceived was to get out of my studio.

I had had enough of being locked away in an upstairs workspace, exiled

to some degree away from social interaction and customary activity. I wanted to blast music from the downstairs

stereo while I painted and experience, peripherally at least, the daily comings

and goings of my wife and children.

Probably more important was the fact that though the lighting in my

studio is ideal for someone painting in a fixed area, it was less conducive to

illuminating a model. After years of

trying, I had yet to find a way of satisfactorily lighting my paint surface and

my subject matter. The room was simply

too cluttered with paintings, pads, easels and art materials to provide a lot

of maneuvering space, and the only natural light was provided by one

double-hung window with a southern exposure.

I guess if Virginia Woolf needed “a room of one’s own” for her creative

efforts, I needed a bigger, brighter one for mine. Moving downstairs allowed me to investigate a

number of locations with unique lighting conditions.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Kitchen Self-Portrait - 2018 |

In executing my next self-portrait,

I was determined to maintain control of my efforts. After penciling in a light sketch, I used pen

and ink to fix detail; then I applied color in thin washes, incrementally

building up tones. I was too tentative,

the resulting image developing into essentially a toned drawing. To mix it up a bit, I worked this time in our

dining room directly beside a window, portrayed myself head-on rather than in

three quarter view and donned an eccentric earflapped hat to boot.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Self-Portrait in Earflapped Hat - 2018 |

So it was back to the drawing board for me. As with the second work, in this image I retained the pen

and ink drawing and jettisoned the underpainting but now was more committed than

before to working loosely. I also wanted

to use bolder colors to suggest form. To

my advantage, I had already gained a partial understanding of how gouache

behaved and recognized that limiting my palette would be advantageous. For this portrait, I wore my black hoodie,

allowing the hood to cast dark shadows over my face. This time I set up my easel in the hallway

beside the side entrance to our home.

Outside light entered through the door’s glass insert, but I was

predominantly lit by a harsh incandescent globe light directly over my head. I chose to stand for this painting because

only in this position could I get the light right. I started at nine in the morning and finished

up at seven in the evening, only stopping briefly for a quick bite to eat at

midday. Not until I walked away from the

easel did I realize that my hands were shaking and I was a bit dizzy. I had definitely pushed myself with this

work…at least, physically so.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Hooded Self-Portrait - 2018 |

For the next portrait, I

wanted to paint myself in profile. It

took some effort to arrange two mirrors in the precise positions required to provide

an acceptable side view. I started with

a pencil sketch before moving to pigment.

Maintaining a consistent pose proved rather difficult since I was

working from a reflection twice removed, and my drawing and painting suffered

for it. After working several hours, I

decided that I couldn’t salvage this painting and called it a day.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Unfinished Self-Portrait in Profile - 2018 |

I felt that one of the

problems with the previous painting was that I didn’t start work with a formal

conception, meaning that I was relying totally on a visual presentation and was

not applying an intellectual structure to the image. So as I regularly shifted position and

struggled to regain my original pose, my perspective kept varying, contributing

principally to an unsuccessful representation.

Therefore I began my next self-portrait by drawing a series of

perspective lines on my watercolor paper.

I chose to use what I would call an extreme perspective, one that might

be obtained by a mosquito flying directly in front of my face, then I drew my

portrait, forcing my features to conform to my perspective guides. Again to provide some variety, I wore a

knitted winter cap for this portrait and can attest that as the spring season

brought warmer temperatures I began to regret that choice. After producing a rough sketch in pencil, I

used pen and ink to fix the detail. I

had wanted to record my pen and ink drawing before painting but forgot and had

already painted in the eyes before taking my photo. Oh well, you can get the general idea.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Preliminary Drawing - 2018 |

I had purchased a larger

watercolor pad prior to my start on this work, and the larger format definitely

facilitated my efforts. All of the

earlier paintings were completed within single day sessions; but numerous days

of work went into this piece. I was back

at the kitchen window, and, having marked with labeled masking tape strips the

positions of my easel, mirror and chair, I could set up my work area each day

precisely as it was when I had started.

I carefully applied semitransparent layers of gouache to my drawing. The heightened coloration and exaggerated

perspective reminded me of some Early Renaissance works, so I thought it would

be fun to insert a sprawling landscape in the background. A photograph I had recently taken while hiking

on the Appalachian Trail served as the ideal

source. Just as with my head, after drawing

in the detail with pen and ink, I applied gouache in thin layers in my

landscape. The resulting image is

awkward and disconcerting, but I’m inexplicably satisfied with it.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Self-Portrait in Knitted Cap - 2018 |

I still wasn’t fully certain

that I was using gouache as intended, so I went back to the internet and

watched more instructional YouTube videos.

In one of them, a woman cautioned against using cheap paints, singling

out Reeves as a prime example of a substandard gouache. Of course, I had been using a Reeves set of

18 colors in the execution of all the previous works. I’ve never been an advocate of the use of

topnotch materials; in fact I often deliberately purchase very affordable

supplies because I can use them more aggressively, without concern of the

cost. For instance, I intentionally seek

out cheap brushes because I like to beat the hell out of them when painting and

don’t care if I go through five or ten in the creation of a single work. But I guessed it couldn’t hurt to give a

better quality paint a try. For about

$25, I ordered a set of Winsor & Newton paints which included the following

6 colors: black, white, red, blue, yellow and green. The set was pretty basic, but I wasn’t too

concerned - after many years of oil painting, I’m pretty adept at mixing

colors. I would have to say, after using

the Winsor & Newton colors on the following self-portrait, that they did

cover better, didn’t become murky and could establish reasonable highlights

over underpainting. Purchasing them was

definitely a wise investment.

Even

though my earlier attempt at a portrait in profile was an unquestionable

failure, I did like the format and wished to give it another try in the future. But I didn’t want to use the double mirror

technique again, so I cheated a bit and took a timed selfie under my glaring studio

lights. I posed in a hallway before a

white wall, lit from behind, my face in shadow.

To keep it interesting, I contorted my face in a fierce snarl. Thankfully, I got from the photos exactly

what I was looking for. After sketching

my likeness in pencil and spending several days painting, I completed work on

the image below.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Snarling Self-Portrait in Profile - 2018 |

I am uncertain as to what

I’ve accomplished with this series. I do know that I’ve achieved some level of

mastery in the use gouache. However I

also wonder if these works form any cohesive statement or merely represent a

string of independent experiments. I

believe I may have suggested earlier on in this entry that my choices of

headgear and facial expression resulted from my simple desire to provide some

variety and technical challenge to my efforts.

But then again I’m sure you could ask a thousand artists to paint a

series of six self-portraits and not one would come up with the same array of

imagery. Surely there is something of

myself in each of these self-portraits.

And perhaps approaching them as technical trials freed me from self-consciousness

and allowed me to more fully express my inner workings. Who knows?

(Considering this bizarre sampling of imagery, maybe I should be less

than enthusiastic about admitting this.)

I have a particular weakness

for self-portraits. If we can agree that

all art whether portrait, landscape, still-life or abstraction is a visual

representation of the artist’s persona, it naturally follows that a self-portrait

is most conducive to a successful and penetrating expression of that persona. Interestingly, some artists (Gustav Klimt ,

for instance) never painted a self-portrait, while others like Rembrandt and

Van Gogh arguably achieved their greatest results while peering at themselves

in a mirror. The intimacy of self

evaluation may have repulsed some artists while others found it intensely appealing.

In

light of my affection for self-portraits, I thought it would be fun to take a

look at some of my favorites and provide a little informal commentary along

with the images.

|

| Edvard Munch - Self-Portrait with Cigarette - 1895 |

|

| Max Beckmann - Self-Portrait in Tuxedo - 1927 |

A century ago, it was very important for artists

to assert their professionalism and refinement.

Historically, artists were viewed as craftsmen or artisans and not as

intellectuals. There actually is an old

French expression “bête comme un peintre” which translates as “dumb as a

painter”. In the firmly structured caste system of late

nineteenth century society artists struggled to achieve respectability and

status. As strange as it may seem,

artists commonly worked in formal attire.

And, of course, the addition of a smoldering cigarette in hand would

have suggested the ultimate in sophistication back then. It’s interesting how similar these two works

executed thirty years apart are. But

while Edvard Munch presents himself as haunted and spectral, Max Beckmann displays

a concrete and confrontational presence.

|

| Gustave Courbet - The Desperate Man - 1844 to 45 |

|

| Gustave Courbet - Bonjour Monsieur Courbet - 1854 |

Regarding nineteenth century artists striving

for respectability, it’s interesting to compare these two paintings

by Gustave Courbet. At the age of twenty

five, he sees himself as a desperate man, perhaps one on the verge of madness. Most likely, the economic and emotional

stress of being a social outsider has taken quite a toll on him. A decade

later, he has achieved some recognition and even depicts himself being

respectfully greeted by a gentleman on the roadside. The gentleman doffs his hat to him, while

Courbet tilts his head backward, causing his beard to be thrust confidently

outward.

Some artists deliberately

denigrate themselves, defying the urge to achieve acceptance and respectability.

|

| Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Self-Portrait with Model - 1910 |

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

establishes himself as a Bohemian, his nude form barely draped in a colorful

robe - his model, clad in lingerie, is not a paid worker but an intimate

associate.

|

| Egon Schiele - Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted above Head - 1910 |

In the same year, the

Austrian Egon Schiele portrays himself as a degenerate, an individual gripped

by animal urges. His hair is an unruly

mane, and his raised arm exposes a scraggly tuft of underarm hair. His leathery flesh is scarred with

lines. Scarcely shrouded by atrophied

muscles, his skeletal frame protrudes awkwardly through his skin. There is a wariness and carnal blankness in

his expression.

|

| Chuck Close - Big Self-Portrait - 1967 to 68 |

Chuck Close would suggest

that he unemotionally reproduces the exactitudes of a photograph without regard

for his subject matter, but, of course, that’s not true. I’m sure that Close carefully selected the black

and white source photograph for his Big Self-Portrait

with the intent of shocking his audience with his own repulsiveness. He portrays himself unshaven, his greasy hair

uncombed, a cigarette clutched between his lips. His audience is granted a view up his

nose. His large, plastic horn-rimmed

glasses rest solidly on his protruding ears.

He is the perfect counterculture villain of the late sixties, the

radical nightmare of the establishment, and we onlookers cannot help but be

amused at how ruthlessly he documents his slovenly appearance. And, by the way, if you’ve never seen this

painting, you might be surprised to learn that it is extremely large, nearly

nine feet tall and seven feet wide (which only intensifies the comic absurdity

of the image).

|

| Alice Neel - Self-Portrait - 1980 |

This is Alice Neel’s only

painting of herself. Unconventionally,

she chose to record herself nude at the age of 80, four years before her

death. She coldly documents the impact

the passing years have had on her form.

A mass of white hair crowns her head, and her sagging breasts droop over

her swollen belly. But, as with all of

her portraits, Neel takes a humanist view of her subject. In spite of her humiliating situation, she

maintains an undeniable dignity. Her

eyes are sharp and alert as she studies her features; her mouth contorts in a

frown of concentration. She returns the

viewer’s gaze quizzically, as if to ask, “And you don’t think this will happen

to you?” (Excuse the digression, but I

wish to relate an unusual connection I have with this painting. In 1981, Neel had a solo show at SUNY Stony

Brook’s Fine Art Center

Often how an artist views

him or herself is determined to a very great degree by the aesthetic

predominating in the era during which he or she lives. For instance, Philipp Otto Runge portrays

himself as the ultimate Romantic figure in 1810. With his soulful eyes, sunken cheeks,

generous lips, unruly hair and upturned collar, he could easily pass as the

hero of one of Byron’s poems. And I’d

bet that Runge believed himself to be presenting a very personal image of

himself rather than a Romantic archetype.

That’s the way we are swayed aesthetically; it’s really quite insidious.

|

| Philipp Otto Runge - Self-Portrait - 1810 |

In the era of Modernism,

conventions changed rapidly and within a few short years the aesthetics

influencing how artists filtered reality could transform dramatically how they

viewed themselves. Käthe Kollwitz

embraces an Expressionist idiom, striving for an essential image that eschews

intellectual sophistication and aims for emotional density. She records her image in a woodcut, a

difficult and physically demanding medium which had been in use in Europe from the late Middle Ages through the end of

sixteenth century but was abandoned for less challenging printing techniques. She depicts just her visage, indicating her

hair minimally and omitting any evidence of the neck or shoulders upon which

her head rests. The print is in black

and white, and there is no attempt to conceal the rough cuts used to fashion

the image. The superfluous and the

pretty have been eliminated, leaving only the indispensable and elemental.

|

| Kathe Kollwitz - Self-Portrait - 1923 |

Henri Matisse was one of the

founders of Fauvism, another dialect of Expressionism, but, in the hands of the

French, Expressionism had a very different flavor than the German variety. For Matisse, Expressionism was essentially

about making aesthetic decisions that commonly violated established conventions

in order to achieve an extremely sophisticated visual language. As with Kollwitz, he has pared down

information to a minimum in his self-portrait, but Matisse is seeking to achieve

a perfect balance between line and form, between technique and illusion in his

work. And, most critically, he uses

color non-naturalistically, employing a heightened palette while realizing a precarious

harmony between tones. Kollwitz’s

self-portrait is a primitive beacon, a timeless totem, while that of Matisse is

a flawless arrangement of line and color.

|

| Henri Matisse - Self-Portrait in a Striped T-shirt - 1906 |

In 1948, Frida Kahlo adopts

the principles of Surrealism in creating her self-portrait. She wears a traditional Tehuana headdress

which isolates her facial features against an intricately patterned web. Certainly, most viewers of this work could

not identify this regional Mexican dress and would only see it as bizarre and

other-worldly. There is no attempt at

modeling here. Her face is nearly

uniformly lit, and the lace work is recorded in almost manic detail. Her exotic outfit, the floral patterning in

the lace, the cartoony tears that fall from her eyes, the mesh of plant life

seen behind her head and the bird imagery in her necklace suggest a symbolic

interpretation that the viewer is unable to grasp. All we are able to glean from this work is

that this is a very unusual portrayal of a pained woman with roots established

in both the natural world and traditional Mexican culture. From this starting point, the viewer is free

to create his or her own fantasy.

|

| Frida Kahlo - Self-Portrait in Medallion - 1948 |

I’m truly amazed when

examining the following two self-portraits executed by Pablo Picasso. In the first, Picasso has fully appropriated

the Symbolist-Expressionist language which was still relatively new in 1901. He presents himself set amongst intense blues

and grays, only his harshly lit face animated by pale flesh tones and rose

colored lips. Something of sickness and

death wafts about this figure, but there is also a spark of intellect in his

features to counteract this perception.

Within a mere six years, Picasso has developed a personal language that

will become known as Cubism. In the 1907

self-portrait, Picasso’s face has become distorted and masklike; his features,

particularly the eyes, are emblematic. The

image is composed of a series of repeated diagonals which fracture space and

defy a traditional spatial interpretation.

Picasso has made the leap from imitation to innovation.

|

| Pablo Picasso - Self-Portrait - 1901 |

|

| Pablo Picasso - Self-Portrait - 1907 |

In self-portraits, artists

consciously select precisely how they appear, what they wear, their facial

expressions and their locations.

Brushwork, paint texture and tonal range are of equal importance.

|

| Rembrandt - Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-up Collar - 1659 |

In his self-portrait of

1938, Pierre Bonnard opposes Rembrandt’s approach to portraiture. Bonnard’s face is in shadow, his expression

nearly indiscernible. His form, small

and insignificant, merges with background elements, a network of repeated

verticals and horizontals. His clothing

is ordinary and unpretentious. He

appears to be wearing a robe over a white undershirt. The artist does not disguise the fact that he

is seeing his image in a bathroom mirror.

This is the mundane image of a man going through his everyday

rituals. Bonnard is just another

compositional element is his endeavor to document in light and color the quiet

sanctuary he has established for himself in his small house on the

Mediterranean. While Rembrandt presents

his circumstances as unique and specific, Bonnard takes solace in the

universality and anonymity of the life he leads.

|

| Pierre Bonnard - Self-Portrait - 1938 |

|

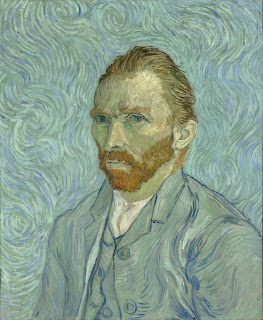

| Vincent Van Gogh - Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin - 1888 |

|

| Vincent Van Gogh - Self-Portrait - 1889 |

It’s funny to consider that

Lucian Freud was a very private painter who wanted to avoid the possibility of

his personal life impacting on how his artistic production was perceived. He was nearly impossible to reach and gave

very few interviews. Even some of his

children didn’t have his phone number. But

for a man who wanted to retain his anonymity, Freud seemed bent on establishing

himself as a conspicuous personage.

Though he was only married twice, he had numerous affairs, some

estimating the number of his lovers to be close to 500. Fourteen children that he fathered can be

documented, but that number may be much higher.

Some of his children had no knowledge of the existence of the

others. Freud painted sexually explicit,

nude portraits of volunteer models including several of his own children. These paintings stressed the animal essence

of his subjects and sought to pierce their civilized façades to reveal their

inner workings. Sometimes he portrayed

nude models along with dogs or rats or used extremely obese models for his nude

figure paintings. He was an unquestionable

eccentric, a regular gambler and workaholic.

He frequently got into conflicts with the galleries that represented him

and even became belligerent with strangers on the street. He lived in unusual circumstances, allowing

his studio and living space to become cluttered with painting supplies, drop

cloths, dirty clothes, newspapers, food containers and other trash. In this magnificent upper body self-portrait,

Freud portrays himself in his mid-60s, shirtless, crusty and irascible,

seemingly substantiating the public’s perception of him that he tried

assiduously to elude.

|

| Lucian Freud - Reflection - 1985 |

Contemporary Norwegian

artist Odd Nerdrum also has a reputation as an eccentric. While a student at the Art Academy of Oslo,

Nerdrum became obsessed with the art of Rembrandt and Caravaggio and rejected

the principles of Modernism. He clashed

with his instructors and fellow students who wished Norway

Initially, Nerdrum painted

dramatic images of contemporary events: the death in prison of Andreas Baader,

Vietnamese boat people, victims of abuse and sensational arrests. These works addressed political and social issues

and, in my opinion, are unsuccessful and would have been ignored. With time, Nerdrum began to present images of

an imagined world that may exist in a time long past or a post-apocalyptic

future. This primordial world is inhabited

by men and women dressed in flowing robes, animal skins and peculiar headgear

who carry weapons, engage in primitive rituals, drink from stagnant pools and

defecate communally in natural settings.

Nerdrum paints amputees and disemboweled corpses…nudes and

hermaphrodites…bricks and babies swaddled like sausages…a flayed ram and decapitated

horse heads…warriors, cannibals and mendicants, which I suppose sounds

pretty…well, odd; except that the technical virtuosity with which the artist

executes his paintings demands that the viewer take his subject matter

seriously. I believe Nerdrum is

constructing an elemental world in which human emotions and motivations are

unambiguously exposed as opposed to the circumstances within our modern society

in which these things are deliberately cloaked.

In 1997, Nerdrum outraged critics and connoisseurs by admitting his work

was just kitsch, disassociating himself from “high art” because he continues to

be committed to the narrative, emotional content and fine craftsmanship, the

antithesis of what he sees as the Modernist credo.

|

| Odd Nerdrum - Frontal Self-Portrait - 1994 to 95 |

In Woman and Art: Contested Territory, a book which explores gender

bias in art and the art world, Edward Lucie-Smith criticized this self-portrait

by Stanley Spencer as expressing the male painter’s determination to possess

his female model. Before going any

further, I must question why this desire on the part of the artist should be

viewed as negative. Surely, many an

artwork has been initiated through sexual desire; and if this painting

accurately reflects Spencer’s mindset, should we disregard it or hold it in

disdain. Why would we proscribe a basic

human drive? It seems that to apply a

blanket approach to such a complex issue is counterproductive and

misleading. To give Lucie-Smith credit,

he does admit that this painting results from a rather bizarre biographical

history and addresses themes beyond the desire for sexual possession.

Spencer was married with two

daughters when Patricia Preece entered his life. She was a bit of a flirt and soon had Spencer

twisted round her little finger. The

artist traveled with Preece and showered her with gifts, going so far as to

sign over the deed to his home to her.

Finally his wife, no longer able to tolerate the situation, divorced

him. That freed Spencer to marry Preece,

who had never ended her long-term lesbian relationship with Dorothy

Hepworth. According to accounts, Spencer

was excluded from his marriage night bedroom which was occupied by Preece and

Hepworth; and the two women went off on a honeymoon while Spencer remained

behind to finish a painting. It’s

believed that the marriage was never consummated. So the circumstances Spencer documents in

this work are very complicated.

Plainly Preece’s nude form

is on display here and could be construed to affirm a sexual connection to the

artist...as a kind of trophy of his conquest.

But there are some major clues that something is off here. The artist is also portrayed unclothed,

atypical for one wishing to express dominion over a lover; on the contrary, it

places the two individuals on an equal footing.

And Preece is not presented as a centerfold model. At the time of this painting, Spencer was 46

years old and Preece 43. Both are

showing signs of decline. Preece’s

sagging breasts display furrowed nipples; her iliac crest juts out from her

hip. Her dark eyebrows are unmistakably penciled

onto a face defined by dipping valleys and swelling hillocks. Spencer doesn’t fare any better under his

scrutiny. His boney back is capped by an

unnaturally long neck. Beneath a strange

bowl cut, he sports large, round spectacles; his weak chin dissolves into

drooping jowls. Preece, appearing bored

and detached, looks away from the artist.

Spencer is alert and aware, one could even say aroused. This is definitely not a work about fantasy;

it describes the complex relations between two very real people. There is no conquest here, only unrequited

desire on his part and unenthusiastic compliance on hers.

|

| Stanley Spencer - Self-Portrait with Patricia Preece - 1937 |

So having examined quite a

few of my favorite self-portraits, a number of general observations have been

made. Some artists paint themselves to

assert their legitimacy and respectability, while others do so to expose

themselves as outsiders and dissenters.

Often a self-portrait is used to declare the artist’s allegiance to a specific

movement. At times, an artist’s lifestyle

(or perhaps I should say life story) is so compelling that it is nearly

impossible to separate image from biography, the self-portrait becoming merely illustrative

of the salacious myths which have taken root concerning an eccentric

personality. I’m certain that most of

the self-portraits presented here served a therapeutic function for the

artists. In open opposition to the

accepted mores of his times, Schiele needed to reveal himself as a sexual being

wracked by animal urges. Kahlo wished to

express the suffering she experienced from her unsuccessful marriage with Diego

Rivera, while Spencer felt compelled to document his complicated relationship

with Preece. Rembrandt proclaims his

disillusionment and exasperation with a world that has refused to recognize his

genius. Van Gogh expresses a crippling

alienation from his society as he struggles in vain to maintain his

sanity. Neel explores the disfiguring

changes that time has inflicted on her body as she anticipates her inevitable

demise. Hopefully each of these artists

gained some solace and healing through this process of self-revelation and

self-analysis.

As for my series of

self-portraits, I’ve depicted myself in many different guises. I’ve appeared harried and anxious…ridiculous

and clownish…dark and diminished…distorted by rage. There are echoes of Close’s willingness to

mock himself and Kollwitz’s somber self-examination in these works. I had no

intention of displaying these works publicly, so egoism doesn’t intrude

here. I’m painting alone in the privacy

of my home, my public persona banished.

Technically, each of these works is flawed. Though I did make some progress in mastering

the medium of gouache, I didn’t come close to attaining the fluidity and

spontaneity I was seeking. I am

undeterred though and will continue to experiment with the medium in the months

ahead. I think there’s one thing that my

readers and I can agree on: we’ve seen enough of my ugly mug, and it’s time for

me to move on to other subject matter.

With the warmer weather having arrived, perhaps some plein air

landscapes will follow.

As always, I encourage

readers to comment here. If you would

prefer to comment privately, you can email me at gerardwickham@gmail.com.