Before

leaving his job, my father had become a bit dour and subdued, more

inwardly focused and less willing to engage actively with others. His

pre-retirement personality didn't emerge overnight but instead

evolved over years. The stress of work, financial worries and health

issues certainly contributed to his less than rosy weltanschauung. My

father belonged to the “Greatest Generation”, the soldiers who

had fought in WWII, and these veterans did not vent about their

emotions and anxieties, instead choosing to stay silent and shoulder

their troubles as best they could. And my father was definitely even

less talkative than most of his male peers. I can recall a number of

occasions when I had messed up terribly and got caught red-handed

violating my parents' rules. Days would pass while I awaited their

response, tension building with each passing day, until finally my

father would address my offense. First he would recount what he had

been informed of my activities in one or two short sentences and then

ask if that synopsis was accurate. When I'd admit that it was true,

he would look sad, never making eye contact with me, and quietly ask,

“Well, that isn't going to happen again, is it?”, to which I'd

sheepishly reply, “No, it won't.” End of discussion. It was far

worse than if he had harangued me for hours... and far more effective

too.

His

innate reticence had been clearly compounded by his recent

experiences at work. His last boss was a high-strung and ambitious

megalomaniac who crafted his management style on the conduct of

Mussolini. He would sarcastically pester my father about retirement,

making it obvious that he wanted him out of the office. Even when my

father was

sixty-five years old, he still needed to work an additional year

before the mortgage on the family home was paid off; leaving

employment before satisfying that loan was an impossibility. Also,

after over three decades with his company, my father had been granted

a private office in which to work, but this boss took that away and

converted the space into a conference room – a humiliating blow for

my dad. Surely his boss's most egregious crime occurred the first

time my father was in the hospital undergoing stomach ulcer

treatment. During his stay at the hospital, my father received a

visit from his boss and another coworker, and, even though my father

had been absent from work for only a short period of time, his boss

felt compelled to inform him that an extended leave would mean that

the bureau would have to take possession of his company car. Though I

believe that current medical thinking may contradict this, back in

the eighties, it was the consensus that stress, if not the direct

cause of ulcers, greatly exacerbated their symptoms. To threaten a

patient undergoing treatment for ulcers with extreme consequences

seemed particularly unconscionable.

When

we were kids, my father would have gotten up, eaten his breakfast,

bathed and exited the bathroom before we had stumbled out of our

bedrooms at about 6:30 am. He warmed up his car quite a while as I

would groggily ladle down a bowl of cereal at our kitchen table, then

he was off to work. He invariably returned home promptly at 6:00 pm

and joined his family for dinner. In my parents' bedroom he had

installed a small, blonde wood desk at which he would plug away at

outstanding work files on his evenings and weekends. Looking on as an

inexperienced child, his schedule seemed unacceptably oppressive,

and, even toward the end of his career when his children had

graduated from college and were working, that schedule hadn't

changed.

Another

challenge my father faced at the end of his career was an appreciable

worsening of his eyesight, eventually necessitating cataract surgery

on one of his eyes. After the operation, his pupil, no longer round,

was now shaped like a keyhole, he was required to wear a contact lens

in the impaired eye and, honestly, his eyesight didn't improve

noticeably. His night vision was particularly bad. When picking up my

sister and me at the train station in the evenings, he would drive

quite slowly, hugging the right side of the road to allow other cars

to pass him. We worried that he might inadvertently hit a bicyclist

or pedestrian obscured in the dark shadows at the road's edge. But

driving was a critical component of his job. Hanging up his keys, at

that time, was not a possibility.

So

clearly my father's last years of employment weren't easy for him.

Instead of coasting into his golden years, he was struggling against

adversity and bearing up as best he could against the assaults of an

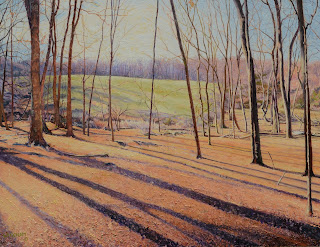

amoral and ambitious supervisor. When during my undergraduate years I

painted my only oil portrait of him, I pictured him with eyes

concealed by reflections and I inserted behind him an invented

background of crisscrossing horizontal and vertical studs (meant to

convey a feeling of complex and exacting structure).

|

| Gerard Wickham - Portrait of My Father - 1981 |

I'm

certain that I've unintentionally presented thus far in this entry a

distorted, uni-dimensional portrait of my father and a far too

harrowing account of his last years of employment. He truly was not

“besieged” during those days. I would say that the hardships I've

described above certainly colored his outlook, making him more

introspective and aloof, but his daily routine remained unchanged and

he plodded through his days impassively. He continued to enjoy the

support of his wife and children, often participating in family

events and visits on his weekends. Regardless of whatever changes I

observed in my father, he remained a faithful, kind, quiet-spoken and

helpful parent.

So I

guess this is where my story begins...

It was

January of 1987, and I had made the train ride from Brooklyn to

Suffolk County, Long Island to flee the noise and bustle of the city,

visit with family and, most importantly, welcome a new addition to

the family: my sister's newborn son. It was cold, at least for

temperate Long Island, and a few inches of crusty snow carpeted the

ground. The family home was situated on a quarter acre parcel in a

very suburban development, and returning there always awakened a host

of memories for me. The place was now both comfortably familiar and

foreign at the same time. I had been living in a Brooklyn apartment

with my girlfriend and working in Manhattan for a while now, and I

always felt just a little out of place when returning home.

Studying

the contents of the refrigerator, I asked my mother what the heavy

cream was for. She replied, “Oh, your dad's doctor has him drinking

that whenever his ulcers act up. It's supposed to coat his stomach.”

“Does it work?” I asked. She just shrugged her shoulders. It was

disheartening to learn that my father was still experiencing

discomfit from his ulcers. I had hoped that his symptoms would abate

once he escaped the anxieties of employment.

My

father had been retired for about a year then, and already I could

see positive changes in his personality. He was alert and talkative

and definitely more relaxed. He frequently laughed, and I was seeing

within him the father of my childhood who would greet me with an

upbeat “Hiya!” when he came up the walkway after returning from

the office. I was shocked to learn that he had begun to patronize the

town's senior center. My father was NOT a participator! I remember my

mother telling me a few years earlier that my father had belonged to

a local volleyball league when they first moved out on the Island

about three decades ago, and I almost fell over. My father was not

athletic, and he certainly did not belong to things. This new

sociability was a very promising development. Considering these

changes, I had reason to conclude that retirement was working out for

him and could only anticipate further gains to come.

Well

after dinner that night, I decided that I wanted to go out and

experiment with my new camera, a Nikon FG-20 recently purchased in

order to make high quality slides of my artwork. So I headed out the

door into the darkness with a camera bag slung over my shoulder and a

tripod in hand intending to take long exposure, naturally lit photos

at various locations in my hometown. I remember that the

ice-encrusted snow made a fantastic reflective surface that picked up

distant, dim houselights and the ghostly glimmer of the moon and I

would lie on my belly behind my tripod hoping to catch the effect.

After a

few hours at my endeavors, I arrived home sometime after 1:00 AM to

find the house brightly lit and still filled with activity. This was

unexpected, and I passed warily through our kitchen's backdoor. My

mother rushed to me and explained that my father's ulcers were

bleeding badly but he refused to go to the hospital. I found my

father in his pajamas and bathrobe standing in our home's sole

bathroom. He was pale and looking weak. I stated that I was going to

drive him to the hospital immediately, but he wouldn't budge. “I'm

fine. I don't need the hospital,” he insisted. I tried

ineffectually to persuade him, but he clearly felt that he could

weather this storm without intervention. My mother pulled me aside

and instructed me to “make him go”. This contradicted my firm

belief at that time in the fundamental right of the individual to

determine his or her own fate - a belief I still hold today. “He'll

let me know when it's time,” I assured her. We lowered the lights

and went reluctantly to bed. I kept my clothes on, stretched out on

the living room sofa and covered myself with a quilt, ready to

transport my father to the hospital in a flash. I hadn't slept a wink

when an hour or two later my father crept into the room and quietly

notified me that he was ready to go.

While

waiting in the emergency room to see a doctor, my father suggested to

me that I should go home and get some sleep. Although he was lucid

and clearheaded, I thought it best that he have someone with him

(even if just for company) and indicated that I would stick around.

After another few minutes, he turned to me and said, “Look, it's

going to be a while before I see a doctor, and, after that, they're

going to admit me. There's really no point in your waiting. In the

meantime, I'll just try to get some rest here.” At that moment, I

was conflicted but eventually succumbed to the logic of what he was

saying and the exhaustion I was feeling. I agreed to go home. Not

that it really mattered much one way or the other, but I've always

regretted that decision.

My

father's prediction was accurate. He was admitted to the hospital,

and, unlike on his previous stay there when they had treated him

non-surgically, the doctors this time determined that part of his

stomach should be removed. Within a day or two, the operation was

performed... successfully, and the next day my father was

recuperating in a room waiting until he was well enough to be

discharged. I visited him then.

He was

in a regular room, shared with one other patient. I recall vividly

the pastel-colored walls, the artificial wood-grained veneers on the

furniture, the plastic accouterments, the high-tech beds. I was happy

to find my father looking well and was relieved to think that, his

problems being behind him, he could return home and live unencumbered

by persistent illness. Though a little weak, he was alert and

cheerful. After a few minutes of the usual hospital visit palaver, he

stroked his chin and winced. “Hey, could you shave me? This stubble

is itching me terribly.” I readily consented, and he directed me to

a cabinet beside his bed in which I found all the necessary gear to

perform this small chore.

While he

held a basin on his chest, I lathered him up, being careful not to

get shaving cream on the hospital linens. Once I applied the razor to

his cheek, I was immediately aware that this shaving job was going to

be a challenge. My father's beard was thick and coarse, the feel of

his skin akin to that of sandpaper. Though in my late twenties, my

facial hair was still thin and downy, easily dispatched during a

quick shave. But I was undeterred. I scraped away at his face,

determined not to inadvertently nick him. I painstakingly applied

myself to this task, regularly changing my position to achieve the

optimal angle to apply the razor. I lifted his nose to get at his

mustache. I asked him to raise his chin, so I could focus on his

neck. I switched from one side of his bed to the other. I loomed over

him. I scrunched down below him. Throughout this long ordeal, my

father cooperated patiently, never losing his cool, recognizing that

I was honestly trying my best. Finally I announced that my mission

had been completed. I grabbed a small towel, wiped the residual

lather from his face and examined the results of my efforts. I was

aghast. He looked exactly the same as before I had started. I

couldn't believe it. I must have held the razor at the wrong angle,

or maybe I didn't press hard enough on it. Whatever the reason, I had

clearly failed to accomplish anything. A tiny giggle bubbled up from

inside me, but I struggled to suppress it. The more I tried to

contain it, the more the giggle insisted it had to be free. I

squeezed my lips together tightly, my face flushing bright red with

my efforts. At first, a few hiccupy gasps escaped from me, but they

soon escalated into something very loud between a keen and a groan,

what I imagine the call of a lovesick moose might sound like. Tears

streamed down my cheeks. I glanced over at my father's roommate to

see him investigating our activities with a terrified expression on

his face, which, of course, only heightened the hilarity. Eventually,

I could contain myself no longer and erupted into a fit of laughter

which literally lasted several minutes. When I had calmed down and

wiped the tears from my eyes, I explained to my perplexed father what

had happened and offered gamely to give it another try. “No,” he

replied, “I think it's just fine. Really.”

From

there, it all went downhill in a long series of internal bleeding

episodes necessitating multiple, ineffective operations and

inevitably concluding with some lethal hospital infection... all

within a three month period. Every time I came to visit, my father

was hooked up to an additional piece of equipment. Eventually his

room in the Intensive Care Unit, where he now resided, resounded with

the wheezing, beeping, clicking, buzzing and screeching of machinery,

monitors and alarms. Unable to communicate due to a tracheotomy, my

father expressed with his eyes what he couldn't with words, and his

eyes seemed to be saying, “Get me the hell out of here!” One

afternoon, I entered the hospital along with my brothers to visit our

father, and we were ambushed by a doctor we'd never seen before. He

was handsome and slick, wore a dashing bow tie and spoke in a soft,

conspiratorial voice. The gist of his little speech was to inform us

that our father had received excellent care and the hospital, doctors

and nurses had done everything possible to treat him and make him

comfortable. He really couldn't say enough positive things about the

magnificent performance of the staff there. We just stared back

totally perplexed. At the end, he asked if we had any questions, and,

when we had none, he trotted off never to be seen again. We looked at

each other, knowing that now all hope was lost, and one of us said (I

really can't remember who), “I guess they're worried about getting

sued.”

At the

end, the doctors informed us that they could not operate again. As a

last-ditch effort, they would try a robust infusion of Vitamin K

which might help to stem the internal bleeding which had plagued him

since his initial operation. Strangely enough, it worked. But at that

point his health was completely compromised and his body beset with

infection. My father died near the end of March.

I

believe people process loss in different ways. Some people simply

collapse, disassociating from reality, surrendering completely to

their grief. Some people may find the whole death ritual to be

cathartic – you know, the demands of making arrangements, meeting

with funeral directors, getting dressed up, attending religious

services, organizing meals, and gathering with friends and family. At

a bare minimum, addressing all those responsibilities provides a

distraction. My family tends to be a bit pragmatic, objective and

dispassionate. I recall that during the weeks before and after my

father's death, my siblings and I gained some comfit from engaging in

a lot of finger-pointing. Of course, we couldn't help but wonder what

would have resulted if my father had received that Vitamin K infusion

even before the first determination to operate was made. We analyzed

every decision the doctors made, finding fault with most of them. If

only they hadn't... Why didn't they try that earlier... Shouldn't

they have... Don't get me wrong, a lot of pretty big blunders seemed

to have been made in my father's treatment, but I also believe that

we lacked the expertise to productively evaluate the judgment of the

medical professionals. We even questioned the choices my father had

made: why hadn't he switched doctors... why hadn't he been more

aggressive in addressing his ulcers... why did he hold off seeking

treatment during this last episode? It took me years to recognize

that our bodies have a shelf-life, and often, despite our tweaking

and fiddling, nothing we do is going to extend or shorten that

shelf-life by much. It's reality. I know death is a hard thing to

face. We really want to believe that by being proactive, by staying

on top of all the latest medical guidance, by making wise choices and

by heeding our bodies' warning signals we can put off our ultimate

departures – well, let's face it, perpetually. Such thinking is

absurd but very reassuring. I guess we all like to indulge in the

fantasy that we're in control of our destinies.

Once all

the post-death ceremonies were performed and my family had convened

multiple times, informally and in various assortments, to lament, to

agonize, to analyze, to criticize and to, basically, vent, it was

time for me and my girlfriend to head back to our apartment in

Brooklyn and for us both to return to our jobs. In my experience the

real mourning begins once you reestablish your everyday life... when

dark thoughts creep in during your daily subway ride or in the midst

of watching a TV show or while lying awake in bed at night.

Strangely, the “what ifs” that had so dominated my family's

thinking earlier began to diminish and were replaced by a vague

realization that had been troubling me throughout my father's

decline. I felt that at some point during his weeks-long hospital

stay my father had been stripped of his “humanness”... that he

had been transformed into an object (like, let's say, an automobile

undergoing extensive repairs, disassembled to the point of

unrecognizability, its parts strewn across the garage floor)... that

his emotions, his feelings, his discomfit, his pain were

insignificant and only the successful outcome of his treatment

mattered... that we, his family, as healthy, functioning individuals

still merited an attention, a consideration and the right to make

choices that he had somehow relinquished – and that was the case

even though he remained conscious and aware throughout most of his

ordeal. And though fully cognizant of what was transpiring, we, his

family, were completely helpless and incapable of intervening. This

disturbed and terrified me.

As is

still the case today, back then, whenever I needed to address or

resolve some distressing occurrence in my life I turned to art.

Several weeks after my father's death, I decided to make a linoleum

block print documenting his last days at the hospital. Though for

compositional purposes I resorted to some distortion and rearranging,

the print accurately depicts each of the many mechanical devices that

sustained my father's life at that time – so accurately that when I

study the print today it brings back vivid memories of those painful

days. My goal was to so prioritize the gadgets and mechanisms

enveloping my father that his own presence would be diminished,

nearly erased. After cutting the block, I tried printing it in

several colors. On one occasion, having just pulled an image in

black, I got lazy. I examined the block and determined that there was

very little residual ink remaining on the surface, that all the

grooves I had cut were pretty much free of ink. Just to be cautious I

wiped off the block with a paper towel. In truth, I should have

cleaned the block with turpentine, washed it with soap and water and

then waited for it to be thoroughly dry before making a print in a

different color. But, like I said, I got lazy. My next printing was

to be in bright red, hopefully to elicit a feeling of alarm, peril,

blood. I inked the block, applied it to a sheet of good quality rag

paper and, not having access to a press, simply rubbed the back of

the print with a spoon until I was certain that the paper had made

absolute contact with the entirety of the block's surface, the whole

process taking quite a while. When I peeled the paper from the block,

I was immediately dismayed. The black ink, the remaining amount of

which I thought negligible, actually asserted itself forcefully,

dulling the bright red ink and creating an inconsistent mottled

effect. I groaned, ruing the time I had wasted trying to cut corners.

I put the print aside to dry, cleaned the block and quit for the day,

expecting to properly execute the print the next day.

The

following morning, I examined the red print again. The infusion of a

small amount of black ink permitted the structure of the print to

pronounce itself more clearly than if I had used only red, which

would have pulsated on the page. I also liked the surprising grainy

effect the black residue contributed to the print and how the darker

hues emerged irregularly, providing a more nuanced, complex component

to a composition which basically consisted of a series of strong

horizontals and verticals. My incompetent accident actually satisfied

me, and I decided that the print was worth keeping. Ultimately, my

thinking went beyond that. Instead of tolerating my clumsy mistake in

one image, I deliberately recreated the effect in all future

printings.

.JPG) |

| Gerard Wickham - My Father's Deathbed - 1987 |

I didn't

quite know what to do with this print once it was completed. It

seemed too personal to share with others. And it seemed to be too

universal to be of interest to others. (Hasn't everyone experienced a

similar loss of a loved one in a hospital setting?) Though this print

has hung on the wall of my home for about thirty years, I believe it

to be too grim for most people to tolerate on a daily basis. So you

might think my whole endeavor to be fruitless. But I would disagree.

During my schooling, I was trained to be a “fine artist”. As such

I was encouraged by my instructors to put aside issues of affirmation

and marketability and instead follow my own unique inclinations. That is the only true pathway to bringing about meaningful communication.

To this day, I am so thankful to have had this central concept

drilled into me throughout my years of higher education. So although

My Father's Deathbed

remains a challenging, troublesome companion, I have no regrets

regarding its creation. In fact, after thirty six years, it asserts

its presence far more tolerably (almost consolingly) than it did at

the time of its execution. And as I grow older and must envision my

own inevitable demise, I can appreciate that even as a young man I

chose to attempt to represent the perspective of a fellow human

succumbing to death while enmeshed in the apparatus of a well meaning

yet incognizant medical establishment. At a minimum I'm satisfied

that I cared enough to give it a try.

As

always, I encourage readers to comment here. If you would prefer to

comment privately, you can email me at gerardwickham@gmail.com.

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)