When I moved north to the Hudson Valley Long Island ,

you learned to savor the snow because, even though we had our major storms, the

plows cleared the streets quickly and the temperatures moderated by the nearby

ocean wouldn’t tolerate snow cover for more than a week or two at most. So, once settled in our new home up north, I

was pleased to find that snow was more than a transient visitor but a stalwart

companion who demanded respect and attention.

Considering this

introduction, you may be surprised to learn that, prior to my move north, I had

never skied. As a youth, the only skiing

that would have interested me would have been downhill skiing, and Long Island was far too flat for that. In high school, I remember some kids taking

weekend bus trips to northern ski resorts, but financially that was out of my

reach and I was a little too “unformed” to participate in organized social

activities. When I came to the Hudson

Valley two decades ago, I noticed that a lot of people cross country skied and

wondered if I would enjoy participating in this activity, a less exhilarating

cousin of the downhill.

I wanted to give it a try

but was reluctant to invest a lot of money in equipment, lest I discovered that

skiing was not for me. So I found myself

one weekend at the local Ski Haus, explaining to a polite yet unenthusiastic

salesman that I wanted to buy an affordable, bare-bones, off-the-shelf set of

skis, just to get my toe into the water, so to speak. He responded that it wasn’t that simple, that

the skier’s height, weight and, obviously, shoe size had to be taken into

consideration, and he began gathering data.

When he finished, the salesman crossed his arms on his chest, looked at

me dubiously and announced that he would go into the backroom and see what they

had in stock. He vanished through a

curtained doorway, and, for quite a while, I heard rattlings, crashes and

smothered curses before he reappeared with a mismatched set of equipment pieced

together from an assortment of clearance merchandise. The salesman calculated the optimum pole

length for someone of my height and cut the poles accordingly. He rang up my purchase, and, though still

more than I had intended on spending, the price seemed reasonable to me. I paid and exited the store ready to begin

skiing.

After about a decade and a

half of experience, I am still using the same mismatched set of equipment and

will get out skiing on any day I’m off from work when the conditions are

right. Commonly, I wake up before

sunrise and, while still a little groggy, consider whether I want to go out

today or not. My bed is warm, and the

house is cold, the thermostat having been turned low during the night

hours. There is a strong temptation to

roll over and go back to sleep (after all, I’ve gotten up at 5:30 all week; I

deserve it), but there is a voice within that reminds me that only through

exertion can the exceptional be accomplished.

I reluctantly throw the blankets back, stumble out of bed and head for

the bathroom for my morning’s ablutions.

I like to get out of the house by 7:00, though in recent years I don’t

always make it out quite that early. I

load my equipment into the car, barely able to see in the pre-dawn light, and

pick up my breakfast on the way to a nearby State Park at which the authorities

permit skiing on their golf course during the winter months. I eat in the car in the parking lot, while

the light turns from slate gray to aqua and the windows cloud over from my

breath and body heat. I save my coffee

for last, savoring every sip as I admire the winter landscape. Believe it or not, I’m not always the first

skier out in the morning; commonly there will be a car or two in the lot when I

arrive. Breakfast completed, I emerge

from the car to find out what conditions will be like that day. If I’ve made a good choice, the temperature

should be well below freezing (but not bone chilling) and, even more

importantly, the winds should not be too steady or intense. I click into my skis (always a struggle),

take my poles in hand and am off.

Just as I am ready to pack

it in, the light changes, and I turn to the east to see the sun edging above

the cluster of hills that ring the course, casting a golden light on the

fairway. The scenery is instantly

infused with color: the snow glimmering with pinks and yellows, shadows

transformed to pale cerulean. I am stunned

by with the unfathomable beauty that surrounds me. At once, I can feel the warmth of the sun along

the length of my body, and, though the pain in my extremities has not lessened,

I continue skiing further out on the course, knowing that relief will be coming

shortly.

From then on, I can focus more on my skiing, setting a pace that is challenging yet not exhausting. My breathing becomes heavier, my heart rate picking up, but I’m careful not to push myself so hard that this activity becomes unpleasant. Cross country skiing is, basically, pushing off of one ski and gliding on the other, alternating with every “step” as you would when walking. When the snow is right and I’m in a good pattern, the gliding becomes protracted resulting in increased speed. I stop for a moment to catch my breath and look behind me, surprised to find that I’ve crossed the last field in what seems just a few moments. In the distance, I hear an incredible cacophony, the honking of an enormous flock of Canada Geese. Sometimes their soundings seem ridiculous and comical, at other times, poignantly melancholy. This morning it’s definitely the comical, a great chaotic hubbub that reminds me of the unruly crowds that I come across in

I continue on, reaching the

furthest point from my car where a small wooden bridge spans a stream. Ice encroaches on the stream from its banks,

but, at its center, the black water still flows freely, a lazy mist hovering

over its surface. The reddish brambles

that line the stream are encased in rime that blazes golden in the early

morning light. Once across the bridge, I

veer to my left, choosing to hug the edge of the woods to maximize the distance

covered on this outing. The sun has

swung well above the hills now, and I have warmed considerably, my hands and

feet no longer in pain. In fact, my core

is so warm that I pop a few buttons on my jacket and pull my scarf away from my

neck. My muscles are loose, and I am in

a rhythm, unconscious of any effort.

Every now and then, I come to a hill which is a struggle to climb, the

grip of the skis not being secure enough to propel me upwards. Instead, I anchor my right ski by turning it

outwards, use the left to make progress uphill and then bring the right up from

behind with a sort of a jerky hopping motion.

It’s slow going to the top, but I am rewarded with a long coast to the

bottom of the hill, with me pushing with the poles to gain more speed and

extend the ride.

I complete my circuit of the

course in about an hour and a half. When

I return to my car, I see the parking lot now holds nearly two dozen vehicles,

most of them lined neatly in a single row along the western edge of the

lot. As I clean the snow off my skis

before loading them into the car, I watch some of the new arrivals preparing to

get out on the course. Their voices and

laughter carry to me. At this hour, the

park which struck me as solemn and austere upon my arrival has been transformed

by a merry bustle of activity. Once I

have loaded my equipment into the car and closed the hatchback, I stop a

moment, hesitant to leave. I am warm and

comfortable in the morning coolness and am feeling that emotional rush that

comes with exercise. It’s odd how

consistently this happens after these outings, but I experience an inexplicable

sense of satisfaction, almost jubilation, that lingers for hours.

It occurred to me the last

time I was on the course that skiing and painting have a lot in common…at

least, for me. I am often reluctant to

go up to my studio. I resent the isolation,

the cutting off from the communal flow of the household, that painting

imposes. I often malinger about the

house, enjoying a snack or engaging some poor soul in pointless conversation,

in an attempt to delay the start of my efforts.

Eventually I recognize that I’ve wasted enough time and have to get to

work. This is a self-imposed

discipline. I have no deadline to meet,

no audience awaiting with bated breath my next creation. As with skiing, painting is a solitary

pursuit, its rewards anchored in experience and health – in this case, mental

health. Once in my studio, I open the

window, put a CD in the boombox and prepare my palette, squeezing out dabs of

paint from the tubes in a horseshoe pattern and finishing by adding several

sizeable globs of white in the center.

Finally, I mix up a potion of linseed oil, turpentine and varnish with

which I thin my paints. I stop at this

point to assess my work, noting flaws and areas with which I’m

dissatisfied. I hesitate to begin,

feeling like a novice, wondering if I really know how to paint. At first I struggle, the process seeming

arbitrary and artificial, as if I am simply applying paint to a canvas. But then the image begins to assert its own

logic and my labor becomes steady and purposeful. Once in this mode, I become immersed in my

work, my concentration becoming focused and absolute. Time accelerates. I am often shocked when a CD comes to an end,

thinking I had just put it on five minutes ago.

It’s hard to explain the state that my mind is in. It’s definitely engaged, tackling problems

and assessing results, but it is also on cruise-control, a lot of processes

“running in background” without conscious effort. I feel very energized, at times almost

ecstatic, and wonder why I was so hesitant to come up to my studio. After several hours of work, I arrive at a

point in my painting at which, technically, it seems prudent to stop. As I clean my brushes, I become aware that

the room is very cold and my back is aching from hunching over in my seat,

leaning into the painting. If it’s been

a good day, as I stretch and twist before the painting, I admire my work,

satisfied with my efforts, feeling an emotion somewhat akin to that which I

described experiencing after a morning of skiing. Afterwards, when I’m back among my family,

it’s difficult to engage in conversation or focus on entertainment. My mind, still addressing the painting, needs

time to transition.

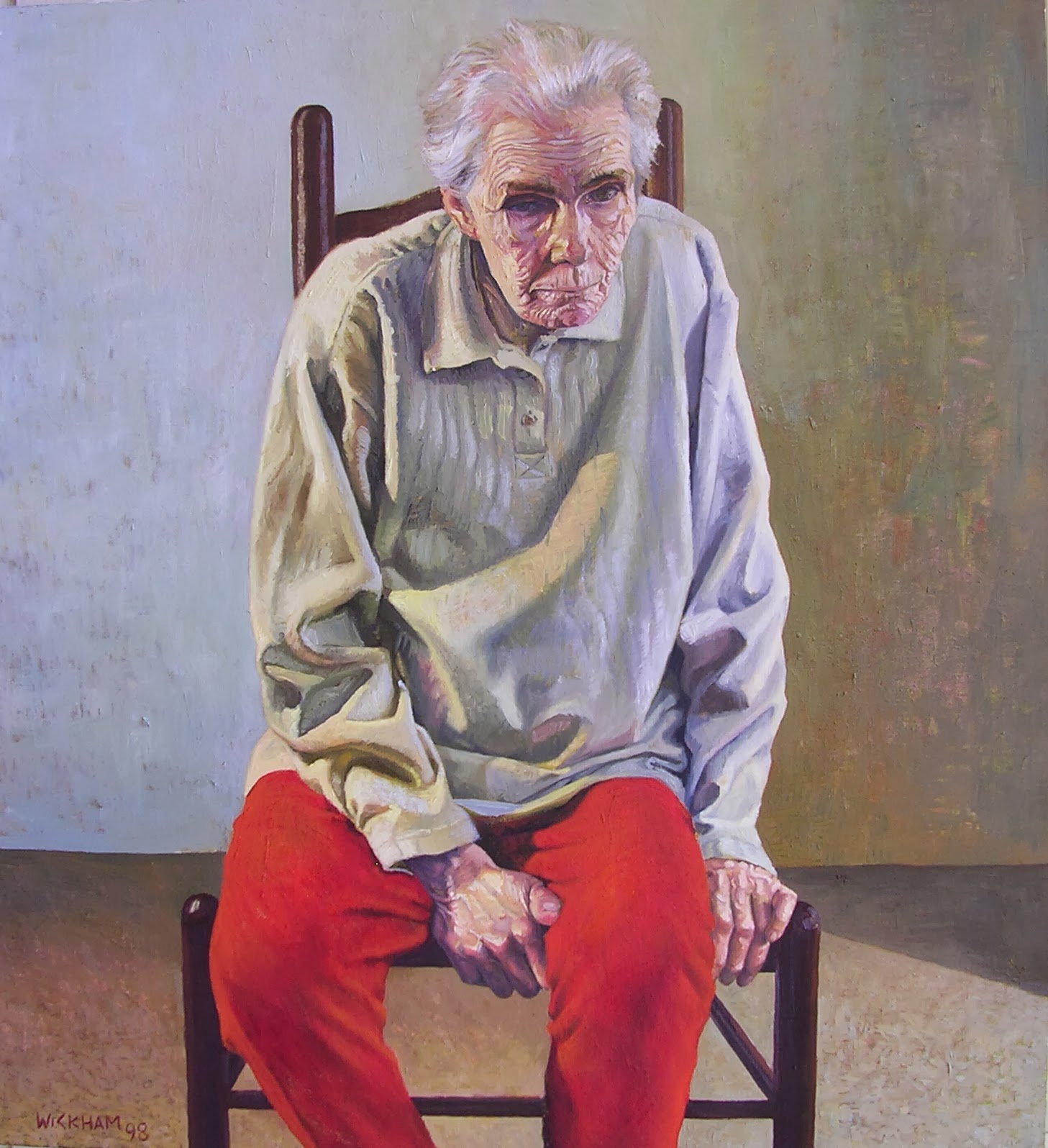

Wickham - Red Pants - 1998

Maybe because painting is

critically important to me, I find parallels to the process in other activities

I pursue. If the season had been summer,

I could easily imagine myself writing a very similar entry with hiking or

bicycling as the topic. On the other

hand (just to prove that I haven’t lost all perspective), I’ve never been in

the middle of a plumbing job or at the end of a day at the office and been

inspired to ponder: Gadzooks! This is a

lot like painting!

Feel free to comment here. If you would prefer to comment privately, you can email me at gerardwickham@gmail.com.