I really don’t like award

shows. And there are so many of them:

the Oscars, the Grammys, the People’s Choice Awards, the Golden Globes, the

Tonys, the Screen Actors Guild Awards, the Black Entertainment Television Awards,

The Country Music Association Awards, MTV Movie and TV Awards, MTV Video and

Music Awards, the Emmys, the Daytime Emmys and the Independent Spirit

Awards. (And I’m sure I missed a

few.) These shows are very long and not

very entertaining at all. I’m lucky if

I’m vaguely familiar with one or two of the nominees in any category. Whatever the genre being honored, I can

pretty much guarantee that I haven’t seen the movie, heard the song or watched

the show. At one time, the Emmys held

some interest for me because I was actually familiar with some of the actors,

actresses and shows nominated, but, of course, inevitably that changed with

time; now the nominations are dominated by HBO and Showtime, two cable channels

I would have to take out a second mortgage on my house to subscribe to – not

gonna happen.

These shows might still hold

some interest for me, regardless of my lack of familiarity with most of the

participants, if the winners were capable of making some sort of cohesive and

engaging acceptance speech. But, almost

without exception, each awardee occupies the podium, looks out to the audience

like a deer in the headlights, blurts out some gibberish which makes me doubt

that word of the nomination ever reached this poor soul and then proceeds to

recite a long litany of individuals who must be thanked – names even less

familiar to me than the very obscure list of nominees up for the award: agents,

family members, acting coaches, collaborators, investors, key grips, hair

dressers and dog walkers. (Really they

may as well be reading an arbitrary list of names from the phonebook. {Are

there phonebooks anymore?})

And, let’s face it,

designating anything as “best” is inherently absurd. Is there a best fruit or a best job or a best

city? No, of course not. We recognize that selections of this sort

come down to personal preference. And

yet we will watch an awards show and actually give some credence to the

selections – rush out to see the Best Picture or purchase the CD of a Grammy

winner. Deep down inside I think we all

recognize that the selections are pretty arbitrary. For instance, Richard Burton, Liv Ullmann,

Max von Sydow, Catherine Deneuve, Peter O’Toole and Cary Grant never won an

Oscar, while Hilary Swank has won the

award for best actress twice. Good god, Forrest Gump garnered the Academy Award

for best picture in 1994; Argo won it

in 2012! Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix, Janis

Joplin, Led Zeppelin and The Who never won a Grammy. In 1997, the Grammy for Album of the year

went to Celine Dion’s Falling Into You,

which was chosen over Beck’s Odelay

and Smashing Pumpkins’ Mellon Collie

& the Infinite Sadness.

Really? Obviously, separating the

wheat from the chaff is not an easy process. It’s certainly impossible

in a diverse society to reach any kind of consensus on what is best – though in

truth I think we can all agree that bananas are

pretty awesome (hey, they come in their own wrappers).

You might ask me why if I

find these shows so lame do I put them on?

Well, actually, I don’t. My wife

does. And I’m certain that she does this

solely out of a sense of social responsibility – you know, it’s a “we’re all

swimming in the same pond, sharing the common experience, ingesting the

identical pollutants” kinda thing. I

know this because, after sitting through an hour or so of any of these programs

(admittedly out of pure inertia), I’ll rouse myself from my lethargy and

proclaim that I cannot watch any more of this nonsense and am going to bed; my

wife will immediately pop up off the sofa, mercifully extinguish the TV,

respond, “You’re right. This is

horrible.” and hurry off to bed, where hopefully a decently crafted book

awaits.

After enduring this

cathartic rant about awards, you will be justifiably surprised to learn that I

intend to perform my own granting of honors right here in this blog, knowing

before getting started that the exercise will be arbitrary and pointless. But I play a little game in my own mind from

time to time that provides a modicum of entertainment for me at those moments

when life doesn’t attain quite the luster we expect of it – for instance,

sitting in traffic, standing on line at the bank or waiting forty five minutes

to see the same doctor who will penalize me $50 for canceling an appointment

without sufficient notice. The mental

game I play is this: I’ll pick a nation and after some serious consideration

and internal bickering will determine who is the greatest painter that nation

ever produced. It’s not a great game and doesn’t provide the same

adrenaline rush that watching a Jason Bourne flick does. But it does keep me occupied. Though I do this just for fun, I am sure

there must be some value in this activity.

We usually evaluate artists as part of a milieu set within a range of

time and relating to a specific movement.

Using nationality as my key determinant forces me to perform a kind of

mental reshuffling of information – placing artists of different periods and

sensibilities metaphorically side-by-side for consideration. Consequentially one can learn about one’s

personal preferences and aesthetics from such an exercise – a benefit

especially important to an artist.

I’ve limited myself to the

consideration of North American and European artists solely because my

educational background and independent studies provide me with sufficient

information to make some kind of tolerable determination. If no artist from a specific nation stood out

as exemplary or if I felt that my knowledge of a nation’s art history was

wanting, I had to exclude that nation from contention for this prestigious

honor. (Is anyone out there up-to-speed

on the Albanian art scene?)

In evaluating an artist (and

let’s be clear I’m referring solely to painters since they share with me the

same area of expertise), I took a number of criteria into account. Foremost, I consider craft or technique to be

important. Stated simply: if the paint

doesn’t interest me, then the artist doesn’t either. Additionally I will recognize innovation or

the influence a particular artist had on the development of the intellectual

zeitgeist of his or her age. Innovation

can also refer to a willingness to tap into personal idiosyncrasies or unique

propensities in one’s work – for in the exposure of one artist’s unfiltered

individuality insight into the mechanism that drives a larger society will

often result. I also think it’s

important that a painter has produced a considerable body of work; there will

be no “one hit wonders” among my awardees.

Finally, it is absolutely crucial that an artist’s output moves me, that

I can connect with it, that it resonates and has a profound emotional impact on

me.

So now that I’ve established

the rules, let’s begin.

Austria – Egon Schiele and

Gustav Klimt are contenders for the title here (sorry, Oskar), but Klimt edges

ahead in consideration of the size of his body of work and how he transformed

the Austrian art scene, nearly single-handedly converting a conservative,

peripheral art community into an influential hub of avant garde

innovation. A century after his death,

Klimt’s very personal imagery grounded in Art Nouveau/Symbolist principles

continues to have a powerful influence on contemporary popular culture.

|

| Gustav Klimt - Der Kuss - 1908 |

|

| Gustav Klimt - Bildnis Friederike Maria Beer - 1915 |

Belgium

– No matter what he painted, James Ensor imbued his subject with the unique sea

light of his native Ostend. His strange mix of pastel pinks, blues and

purples, rusty browns and pure blacks lend his paintings an aura of beauty

tainted with decay. His still lifes of

fish and shellfish are inviting and repulsive at the same time – the sea

creatures, though dead, continuing to impose a living presence on the

viewer. Ensor was fascinated with masks

and make-up, the purpose of which is to cover up or disguise the outer physical

shell of a being, but, paradoxically, in his work these implements of

camouflage actually end up revealing the inner self that the individual most

desperately desires to hide. Often his

paintings serve to expose social hypocrisy, systemic injustice and political

malfeasance. Art permitted this very unique

painter to retreat to his private world of puppets, masks and costumes only to

peer out with a mixture of humor and disgust at the larger outside world.

|

| James Ensor - Skeletons Fighting for the Body of a Hanged Man - 1891 |

|

| James Ensor - Still Life with Blue Pitcher - 1890/91 |

Canada – Emily Carr is a complete anomaly. She was born on the west coast of Canada in 1871

within a conservative Anglophile household, yet she became a true pioneer,

introducing European modernism to her country.

Despite working in relative isolation and suffering the indifference of

the society in which she lived, Carr developed a personal style which combined

elements of modernism and indigenous art and documented the natural landscape

of her homeland. Her fortitude and

independent spirit sustained her during many years of desperate struggle which

ultimately concluded with significant artistic achievement and acceptance

within a community of like-minded artists.

|

| Emily Carr - Big Raven - 1931 |

|

| Emily Carr - Sea Drift at the Edge of the Forest - 1931 |

Denmark – There really is no one else to consider. Vilhelm Hammershoi is an artist who really

did not embrace the modernist revolution.

His execution is fairly conservative, and his technique, I would say, is

competent. It is his vision which makes

his work stand out and lends it a very modern aura. To a receptive viewer, his paintings assert a

quiet yet stirring influence.

|

| Vilhelm Hammershoi - Ida Reading a Letter - 1899 |

|

| Vilhelm Hammershoi - Interior with Four Etchings - 1905 |

France – In recent centuries, the French have recognized

the importance of the visual image as a vital component of intellectual and

emotional communication. Starting, let’s

say, with the French Revolution, Art became the subject of serious criticism,

incendiary newspaper articles and popular discussion. Openings at the Salon were thronged with

visitors, and independent showings by avant-garde artists were greeted with

derision and scandal. Art inspired

nationalism, initiated social change and influence politics. Through the 1950’s, any artist, wishing to

learn his or her craft, become enlightened as to the latest trends in visual

representation and secure artistic credibility, would have to visit Paris for

an extended stay of several years. In

such a fertile environment, it is not surprising that France nurtured

an endless array of exceptional artists, an array so vast that I will not even

attempt to generate here a list of contenders.

Instead I will simply tell you who the best is: Pierre Bonnard. Bonnard’s compositions seem quirky and

intuitive, but upon closer inspection reveal themselves to be carefully and

intelligently planned. For most other

artists, light and dark contrasts are used to establish structure and movement

within a painting; Bonnard uses zones of heightened color. The surfaces of his paintings are exquisite,

varying from thin delicate veils of color to thick encrustations of

impasto. Bonnard’s work documents the

serene, private life he shared with family and friends; it celebrates quiet

moments filled with simple pleasures and pastimes.

|

| Pierre Bonnard - The Bath - 1935 |

|

| Pierre Bonnard - The Dining Room in the Country - 1913 |

Germany – This selection was difficult for me. Lucas Cranach, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max

Beckmann and Anselm Kiefer were in the running, but Kirchner edged out his

competitors based on innovation – his work bringing German art abruptly into

the modern era. Kirchner constructed a

personal language, derived from the art of the Middle Ages, primitive cultures

and modernist developments, with which he expressed both criticism of

contemporary society and an optimism that a utopian paradise was attainable

within an individual’s microcosm if he could discard the shackles of

convention.

|

| Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Seated Girl - 1910 |

|

| Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Self Portrait with Model - 1910 |

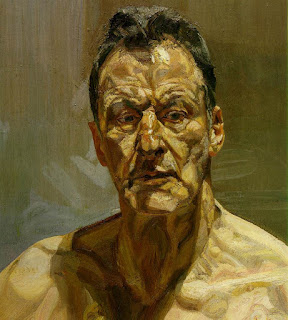

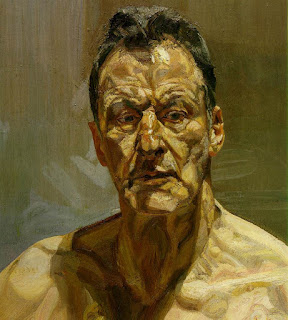

Great Britain – It’s interesting how some nations excel in certain

arts and not others. The written word,

whether within poetry or prose, has been an essential component of British life

since the Middle Ages. Their greatest

composers and artists tended to be imported from other nations. All the same, Britain

did produce John Constable, William Turner and Thomas Gainsborough, artists

fostered by the fairly conservative Royal

Academy. In the twentieth century, independent artists

like Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach were able to establish successful careers

outside of the academy. By far, the most

important painter to mature in Britain

is Lucian Freud, an artist who developed a style which featured an almost manic

attention to detail and nuance while exploring psychological states as exposed

through gesture and expression.

|

| Lucian Freud - Reflection (Self Portrait) - 1985 |

|

| Lucian Freud - Rose - 1978/79 |

Greece

– Though most closely associated with Spain,

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) lived and studied for the first 26 years of

his life in Crete where he attained

recognition as a master and most likely operated his own workshop. Later he worked three years in Venice and seven in Rome

before moving on to Toledo,

Spain, where he

lived the remainder of his days. El

Greco was influenced by Byzantine, Renaissance and Mannerist art but was a true

original, seeking a language which could articulate a spiritual realm only

accessed in the imagination of believers.

The use of distortion, free brushwork, unusual colors, elongated figures

and fantastic landscapes characterized his work which perplexed his

contemporaries and delighted the modernists of the twentieth century.

|

| El Greco - Laocoon - 1610/14 |

|

| El Greco - The Vision of St John - 1608/14 |

Holland – It’s hard not to be an admirer of Rembrandt van

Rijn. After all he was a master of every

genre: landscapes, portraits, large scale multi-figure paintings and

historic/religious paintings. But it

wasn’t until I saw his Christ Resurrected

in Munich’s

Alte Pinakothek that I truly appreciated his genius. A deceptively simple work, this painting

which depicts the head and upper torso of Jesus still draped in his burial

shroud might at first glance be considered the result of a rather uninspired

effort. But upon closer inspection the

magic of the loose and varied brushwork, the rich tonalities contained within

even the flat planes of the torso and the delicately delineated folds of the

shroud amazed me. Jesus’ face, almost

expressionless, examines us dispassionately with the faintest suggestion of

pathos in his eyes. (Don’t even try to

look this painting up on the Internet.

I’ve never seen a reproduction that even comes close to doing it

justice.) In an earlier entry, I’ve

already addressed Rembrandt’s self-portraits, which are simply incredible. I honestly believe if we were left with only

his self-portraits, Rembrandt would still be considered one of the greatest

painters of all time.

|

| Rembrandt - The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild - 1662 |

|

| Rembrandt - Self Portrait with Beret and Turned Up Collar - 1659 |

Italy –

I’ve always been a fan of Umberto Boccioni, and Michelangelo is without doubt

the greatest all-around artist that Italy has ever produced – but best

painter has to go to Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Caravaggio was an incredible craftsman, his

brushwork assured and precise. He loved

harsh lighting and sought subject matter that permitted him to exploit the

dramatic effects of strong lights and darks.

An early adherent to the Mannerist style, Caravaggio preferred compositions

which were quirky, unbalanced and capitalized on the emotional impact of

unusual and exaggerated perspective. Like

his own personality, Caravaggio’s paintings are intense, dramatic,

unconventional and tempestuous, and his innovative imagery influenced artists

throughout Europe for many years after his

early demise.

|

| Caravaggio - The Conversion on the Way to Damascus - 1601 |

|

| Caravaggio - The Incredulity of Saint Thomas - 1601/02 |

Mexico – I’m going to bend the rules here and give this one

to a couple: Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

Rivera essentially invented the Mexican mural – utilizing warm earth

tones, generalizing form and introducing didactic themes which promoted a

communist morality and championed the accomplishments and mourned the sorrows

of an impoverished working class. A

naturally introspective nature compelled Kahlo to paint a series of self-portraits

which explore her troubled existence while embracing a surrealist mode of

representation. Even though she worked

far from the center of the movement, Kahlo managed to fully absorb and

personalize the surrealist dialect.

|

| Diego Rivera - La Vendedora de Alcatraces - 1942 |

|

| Diego Rivera - Mural Depicting Mexican History - 1929/45 |

|

| Frida Kahlo - The Two Fridas - 1939 |

|

| Frida Kahlo - Self Portrait with Hummingbird - 1940 |

Norway

– Seems to me that Norway,

though late to become an independent nation, has a tendency to foster artists,

composers and writers with unconventional spirits like Knut Hamsun, Odd Nerdrum

and Karl Ove Knausgaard. Edvard Munch,

an artist who first explored a Symbolist mode of representation and later

ushered in Expressionism, is Norway’s

greatest contribution to European intellectual theory and one of the giants of

Western art history.

|

| Edvard Munch - Melancholy - 1892 |

|

| Edvard Munch - The Storm - 1893 |

Portugal – Though her work sometimes dips into the pedantic,

Paula Rego deserves recognition as an exceptional contemporary artist who has

created a unique visual language while addressing themes from a feminist

perspective. Her imagery is often

unsettling (at times, quite disturbing) as she examines issues relating to role

play and body image. Also technically

her painting process is transparent, a quality I greatly admire in artwork.

|

| Paula Rego - The Family - 1988 |

|

| Paula Rego - The Policeman's Daughter - 1987 |

Russia – While I’ve always been extremely receptive to Ilya

Repin’s paintings which document so effectively the era which produced Tolstoy,

Dostoyevsky, Chekhov and Turgenev, I had to select Wassily Kandinsky for this

honor. Kandinsky’s oeuvre is technically

brilliant, extremely innovative and packs a powerful emotional wallop.

|

| Wassily Kandinsky - Composition II - 1910 |

|

| Wassily Kandinsky - Composition IV - 1911 |

|

| Wassily Kandinsky - Composition V - 1911 |

Spain – This is a no-brainer. It’s got to go to Pablo Picasso, the Meryl

Streep of art. Picasso could do it

all. He reinvented the way we see

reality and influenced generations of painters through the present. His name is synonymous with modernism.

|

| Pablo Picasso - Guernica - 1937 |

|

| Pablo Picasso - Still life with a Bottle of Rum - 1911 |

|

| Pablo Picasso - Self Portrait - 1907 |

Sweden – It seems to me that Swedish artists consistently

maintained a conservative stance toward artistic innovation throughout recent

history, often assimilating the ideas of new artistic movements decades after

their development. This conservatism

could be due to geographic isolation or the result of centuries of stable

monarchical rule and religious uniformity.

Though his work may not stand out as trend setting, Anders Zorn achieved

a technical perfection and visual honesty which I can’t help but admire.

|

| Anders Zorn - Martha Dana - 1899 |

|

| Anders Zorn - Self Portrait - 1915 |

Switzerland – Ferdinand Hodler wouldn’t be considered one of the

giants of modernism, but I’ve always connected with his work. Technically his oeuvre is brilliant. While embracing a Symbolist creed, Hodler

utilized a bright, clean palette and applied paint in thick, confident

strokes. He was equally adept at

painting the figure and landscape, and regardless of subject matter, his

imagery projects a powerful emotive presence.

Hodler was a true independent.

|

| Ferdinand Hodler - Eiger, Munch und Jungfrau in der Morgensonne - 1908 |

|

| Ferdinand Hodler - Self Portrait - 1916 |

United

States – It was very

difficult for me to choose between Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and

Richard Diebenkorn. De Kooning

definitely achieved a technical mastery in his work, a lushness of surface

combined with brilliant brushwork, that is truly remarkable. Diebenkorn, after absorbing the language of

abstraction, went on to successfully apply that idiom to representational

imagery, developing a totally new perspective on figure and landscape

painting. But it was Pollock who made

the greatest leap from easel and mural painting to drip painting. He changed so much about art. He worked on unstretched canvas laid out on the

floor, used materials not normally associated with fine art and no longer

applied paint to the canvas with a brush.

His gestural drips were guided by subconscious drives and memories. His work redefined how art functions and

determined for decades the parameters of what was permissible for American

artists to address in their work.

|

| Jackson Pollock - Alchemy - 1947 |

|

| Jackson Pollock - Lucifer - 1947 |

Having made public my

obviously astute selections, I anticipate a barrage (in truth, hopefully, a

trickle) of comments questioning my judgement.

“Picasso over Velazquez? Absurd!”

“Hey, Bud, ever hear of a dude

named Rubens?” “You do realize, Fathead,

that de Kooning wasn’t even American?”

Not only will I weather any criticism that comes my way but honestly do

encourage it. As I said earlier, the

value in selecting the “best” of any discipline is that it forces us to

consider the merits and flaws of a vast quantity of work, often to evaluate the

products of disparate genres and milieus alongside one another and to decipher

in the process what are our own preferences and predilections within a given

field of art. Another benefit I failed

to mention earlier is that hopefully the process inspires a productive dialogue

with others about their own views.

So rather than feeling that

my little exercise in selecting best painters by nation was a complete waste of

time, I believe that the process had several real merits. It really makes me want to reconsider my

attitude towards awards and awards shows entirely. They’re really not so bad. I mean, hey!, if

there were an awards show for blogs, I would be thrilled to stumble up to the

podium, bask a moment in the harsh lights, wait patiently for the applause to

subside and then make one helluva dumbass speech.

And the Bloggy goes to…

As always, I encourage readers

to comment here. If you would prefer to

comment privately, you can email me at gerardwickham@gmail.com.