I came across the following quote while researching my

previous entry which concerned Ferdinand Hodler and the Symbolist movement:

“Hodler’s portraits, on the otherhand,

are committed to the contingencies of the world. They refer to the unequivocal and the

evident, to the subject portrayed. All

that is left to discuss are historical details and painting technique.”

Tobia Bezzola

– “Landscape as Consensus Formula”

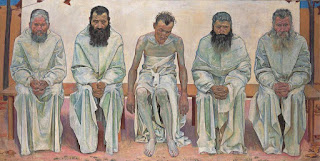

What I love about Art Historians is that they make the most

ridiculous statements and assert them so definitively. In the essay “Landscape as Consensus

Formula”, Bezzola dismisses most of Hodler’s oeuvre, promoting the premise that

only his landscapes and the Godé-Darel cycle remain relevant. He feels that his portraits, too concerned

with capturing the fleeting appearance of his sitters, could only interest us

for the circumstances that led to their creation or for their technical

execution. Obviously, Bezzola does not

adhere to the premise that technique is concept.

Hodler - Self Portrait - 1912

In my previous entry,

I disclosed how much I admire Hodler’s self portraits. The self portrait I selected to include above

exemplifies most of the traits that I appreciate in Hodler’s work. There is a certain élan in Hodler’s approach,

the confident way paint is applied to canvas in thick, impasto strokes, the way

the rapid, loose sketching in paint that initiated the portrait is never

obliterated, that corresponds to my assertion that, in spite of the many hardships

he suffered, Hodler maintained primarily an optimistic outlook throughout his

life. The brushwork dances over the

surface of the painting finding an intuitive rhythm of line and form. In some areas, the brushstrokes are short,

distinct and active, like bees gathered at a hive; in other areas, like the

white shirtfront, seemingly discordant tones are slurred together

successfully. Hodler’s unique palette conveys

an otherworldly luminescence that bathes form in an overall light. I get the feeling that, for Hodler, painting

was a performance in which every movement was decisive and rapidly executed, a

testament to his unparalleled skill. The

artist undoubtedly seeks to restrict detail, finding a shorthand approach to

translate visual reality. For instance,

the hair and beard are indicated very summarily, structure being determined by

two or three tones.

Hodler presents himself frontally and symmetrically, his

head filling the canvas. The artist is

addressing a momentary instant when a specific mood or emotion washes over

him. His face expresses bemused

surprise, as if he has just been confronted with some rather harsh criticism of

his work from an individual completely uninitiated into the mysteries of Modern

Art. It is not too big a stretch to

assert that his expression parallels that of the thrilled girl in Surprised by the Storm. There is something uniquely Swiss in this self

portrait. In the deft handling of the

paint, in the glowing overall coloration, in the image of a well dressed,

carefully groomed man expressing shock unconvincingly, I perceive a smug

confidence and satisfaction, affluence and wellbeing, and a droll sense of

humor.

Freud - Reflection (Self Portrait) - 1985

To further illustrate how technique cannot be extricated

from meaning, I will examine one of my favorite paintings, Reflection (Self Portrait) by Lucian Freud, in many ways the polar

opposite of the Hodler though quite similar in subject matter and

presentation. Technically, Freud is very

tentative. His paintings are executed in

layer upon layer of encrusted paint.

During countless sessions, Freud studies his sitter (in this instance,

himself), evaluating and reevaluating form, pose, coloration and light, seeking

a deeper penetration of his subject and a fuller understanding of

structure. Freud is very hesitant to

commit to a stance, repeatedly reconsidering every stroke he inflicts on the

canvas. Painting, for Freud, is a

laborious and unrelenting process of examination and documentation. Ignoring the subject matter, the piercing

gaze of the artist and the unsettling lack of clothing and focusing solely on

technique, it is unmistakably evident that the Freud has to be a very different

painting from the Hodler.

Portraiture is a long established genre which at its worst

can get real tedious and musty. But innovative

masters have regularly proven that the genre continues to be relevant. Just taking a look at the two following self

portraits, one by the photorealist Chuck Close and the other by the

expressionist Alice Neel, will give you an idea of how much potential

portraiture still offers.

Close - Big Self Portrait - 1967

Neel - Self Portrait - 1980

I must acknowledge that I love self portraits, which may

explain why I paint so many myself.

There is the issue of availability.

Who else would pose for hours in a poorly ventilated studio? And who else would be able to strike the

precise pose required and set the desired expression effortlessly session after

session? Most importantly, painting

yourself frees you from a dialogue with the model, that intrusion of another

voice or perspective which inevitably, no matter how much of a steely renegade

you believe yourself, reverberates within the artist’s mind. So, I have a long history of painting myself

and thought it might be interesting to provide a sampling of a handful of my self

portraits.

Wickham - Self Portrait - Oil on Canvas - 1980 - 30" X 24"

Under the influence of expressionism, I painted this

elemental image of myself, tanned, bearded and long-haired, in thinned washes

of earth tones, blue and black. The

quick rendering of my features in dark umber is very apparent in the finished

painting; the brushwork is loose and intuitive; detail is minimal.

Wickham - Self Portrait - Oil on Canvas - 1981 - 30" X 24"

I included the two previous self portraits in an early show

and a reviewer felt that they were contradictory, that I must be bipolar or

emotionally confused since one painting portrayed a disturbed wild man and the

other an urbane and cultured gentleman.

Without a doubt, I was in a better place when I painted the second self

portrait, but I certainly don’t find the image soothing or reassuring. I was perplexed by the reviewer’s

comments. Both works are essentially

expressionist in vocabulary and depict the artist assuming a confrontational

and troubling attitude.

Wickham - Self Portrait with Deer Hoof -Oil on Canvas - 1983 - 48" X 40"

This painting was intended as one panel of a diptych based

on an absurdist reinterpretation of the Annunciation. The work was never completed, unfortunately,

because my intended model for the Angel Gabriel became uncomfortable with the

project and I didn’t press for her continued participation. Strangely enough, the one complete panel stands

very well on its own merits.

Wickham - Self Portrait - Oil on Linen - 1988 - 18" X 16"

For a period of several years, I only painted abstractly, an

approach that revitalized my art and produced a satisfying body of work, but

eventually painting in this manner became conventionally confining and came to

a dead-end. It was very difficult for me

to walk away from abstraction, and for quite a while I created paintings that

were neither fish nor fowl, toying with clearly recognizable imagery that was presented

in a truncated or mutilated fashion and executed in a painterly expressionist

technique. These paintings, without

exception, are failures, but they did reintroduce me to the possibilities of

representational imagery. I certainly

had no intention at that time to become a figurative or realist artist, and yet

slowly the work evolved in that direction.

This self portrait comes from this strange period when I was a little

lost, just putting my toe in to test the representational waters, so to speak,

but uncommitted to any specific approach.

Vestiges of my abstract experience are apparent in the patterned and

energetic brushwork, the unconventional color combinations, the harsh

transitions between lights and darks and the clearly visible, intensely colored

underpainting.

Wickham - Self Portrait - Oil on Canvas - 1996 - 14" X 12"

I had just gone through a long period of experimentation

during which I painted small frontal portraits in heavily built-up layers of

impasto when I started this self portrait which ultimately signaled the end of

the series. Using thin transparent

glazes of delicate color, I depicted myself in three quarter perspective, the

result being about as close as I’ve ever gotten to embracing a photorealist

technique. This happens with me

frequently. I will tenaciously pursue

one avenue of exploration, setting circumscribed restrictions on technique,

subject matter and approach, painting one image after another for months or

even years, until I have exhausted myself, garnering whatever disclosures the

experience offers. Without

premeditation, a painting that violates all of the restrictions I have been

conscientiously following will cap off the series, usually resulting in a very

successful work that suggests a multitude of possibilities for future progress.

Wickham - Self Portrait - Oil on Canvas - 2000 - 54" X 30"

I’ve never been an artist to flatter a sitter which at times

has led to some uncomfortable moments when a final viewing has met with stony

silence from my model, usually an unpaid volunteer. I recall while in Grad School

Wickham - Self Portrait - Oil on Canvas - 2002 - 16" X 12"

Painted in my studio under a bare incandescent bulb, with

ribbons of black cloth draped in a cocoon around my head, this self portrait

achieved a sense of light as a tangible substance. It was executed in oils, layer upon layer

applied over numerous sessions in various thicknesses from impasto to viscous

to dilute. When completed, the surface

finish ranged from matte to glossy, making it difficult to view as a whole, in

particular, contesting the sense of light I was struggling to capture in the

work. I placed it aside for a number of

years before pulling it out one day to discover that in drying it had achieved

the desired effect.

Wickham - Self Portrait with Camera - Oil on Canvas - 2011

The lighting in my bathroom, a wall bracket of frosted

globes combined with an overhead ceiling fixture, creates a subtle suffused

frontal light contrasted with a strong halo effect which has interested me for

years, but, as for initiating a painting, compositionally I always drew a

blank. One afternoon I noticed that the

two mirrors in the room, one over the vanity and the other set in the medicine

cabinet, were facing each other and created an effect I first witnessed as a

young boy seated in the raised chair at Pete’s Barbershop: the mirrors

contained a repetition of infinite images of me and my surroundings receding

into nothingness. In my bathroom, I

particularly liked that the reflections created multiple framing devices that

bordered my head, creating a confusing and disjunct space. So I grabbed my Nikon and took a series of

photographs which I used to create the self portrait included above. I felt a sort of confessional relief showing

the camera in the painting, as I regularly use photographs as a resource for my

work without the imagery and paint handling reflecting this. Though the debate over whether it is

legitimate to use photographs as a resource for painting or plaster casts for

sculpture is long dead, having been trained to paint and draw from life, I

still suffer a little guilt.

Technically, as has been the case in recent years, I strove to allow the

painting to form organically, utilizing whatever means makes sense for the form

or texture or surface or light effect that I endeavor to replicate. I still utilize an underpainting to heighten

color vibration in the finished work, though the hues are much more subdued

than those I used in the past. I

definitely apply fewer layers and use less paint than ever before, not for the

sake of speed or economy but to assert an authenticity of approach.

I really found it fascinating to select and evaluate this

series of my own self portraits, to witness my growing older while observing my

stylistic evolution. To keep the length

of this entry reasonable, I had to limit my selections, excluding some

satisfying works in the process.

Hopefully, I can revisit the theme in the future, and perhaps, by that

time, I will have produced a new self portrait or two.

-1985.jpg)