I wasn’t familiar with the artwork of Ferdinand Hodler in my youth. The public library in my hometown didn’t have a Hodler monograph, though it did possess an extensive collection of oversized art books. He isn’t well represented in American collections, and I can’t recall there ever being a show at a NYC museum devoted solely to his work (the Neue Galerie’s “View to Infinity” exhibition being a recent exception). In all my years of studying Art History, his name was never mentioned once. One of my textbooks for a survey course did include one black and white plate of Night, which being a quintessential Symbolist work struck me as both magnificent and absurdly stagey. Somehow, over the years, I discovered his work, mostly in reproductions, and came to appreciate this underappreciated master.

|

| Hodler - Night -1890 |

For those of you unfamiliar with Hodler, I will provide a brief introduction. He was born in Berne , Switzerland Geneva

At the time of Hodler’s artistic maturation, artists throughout Europe were rejecting the naturalism of the Realists and the Impressionists, which had defined progressive art in the mid-19th century. Symbolism wasn’t your typical movement, initiated by a centralized, tight knit group of individuals. Though established in France , the movement’s most accomplished proponents were scattered throughout Europe , commonly from nations not then recognized as centers of the visual arts: the Norwegian Munch, the Austrian Klimt, the Swiss Hodler and Böcklin, the Belgian Khnopff and the German von Stuck. Of course, Moreau, Redon and Puvis de Chavannes are significant Symbolists of French origin. There were common themes addressed in the work of these artists who rejected the detached representation of visual realty. The Symbolists sought to pierce reality, to find the common threads that define human existence, leading them to explore allegory. Munch’s nude youth sitting on the edge of her bed is not a portrait of an individual; it is a depiction of Puberty. For Hodler, a nude woman surrounded by six shrouded men is the visual representation of Truth. Klimt’s works include Jurisprudence, The Virgins and Medicine. Hodler painted Night, The Day and Spring, while Munch explored Melancholy, Jealousy, Dance of Life and Ashes. Clearly these artists were seeking the universal in their work, not the specific, not the individual.

Munch - Jealousy -1895

The Symbolists also presented to Victorian Era audiences an unabashed sexuality that challenged contemporary morality. Addressed in an Impressionist vocabulary, Degas’ nudes were shocking for being unsentimental, unidealized and mammalian; on the other hand, they did not embody an active sexuality. The Symbolists seemed hell bent on confronting the smug morality of their epoch. Their nudes were undeniably naked and unquestionably sensual beings. Again, the Symbolists rejected external reality and portrayed the unseen, the individual beneath the clothing experiencing very private urges.

Klimt - Judith I - 1901

Most critically, these artists strove to preserve an air of mystery in their work. A painting should not be grounded in specifics, nor should it be dissectible. A true work of art should project a very personal perspective and elicit a strong response based on its unconventional uniqueness. Often, the Symbolists turned to dream imagery and mythological themes to distance themselves from everyday reality and establish an otherworldly mood.

Bocklin - Centaur at the Village Blacksmith's Shop - 1888

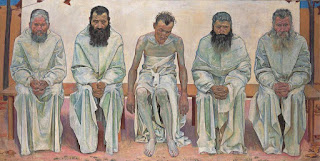

Hodler also embraced his own personal creed which he called “Parallelism”, a method of establishing order within his compositions by presenting repetitions of figures or forms usually organized in parallel planes. This approach can be clearly recognized in many of his landscapes where horizontal bands of clouds repeat in an endless series in the sky or in figurative works like “Those Tired of Life” in which five elderly men are portrayed sitting frontally and evenly spaced on a bench. “Parallelism is more than a principle of formal composition, it is a moral and philosophical idea, relying on the premise that nature has an order, based on repetition, and that in the end all men resemble each other.” (Musée d’Orsay website)

Hodler - Those Tired of Life -1892

Like Munch, Hodler, stylistically, evolved toward an Expressionist outlook, particularly in his later years, but he never fully transitioned to the new vocabulary as did Munch. I think his last portraits of Valentine Godé-Darel most fully embrace the Expressionist approach, perhaps impelled by the intensity of emotion sparked by his subject matter. You see, Hodler was recording over a period of months the physical decline from cancer of his mistress and model, a woman to whom the artist was deeply committed. After Godé-Darel’s death in 1915, Hodler continued to be productive artistically until his own death three years later.

Hodler - The Dying Valentine Gode-Darel - 1915

My interest in Hodler, as is the case with most artists I admire, was initiated through an appreciation of his technical skills because, in the end, technique is everything. As Sam Gelber once told me in Grad School

Hodler - Self Portrait - 1916

In the early 90’s, I was given the opportunity to visit Switzerland Oskar Reinhart Museum in Winterthur

Hodler - Surprised by the Storm - 1886

I visited many museums and collections during my two weeks stay in Switzerland

Hodler - Lake Thun Landscape

Hodler - Portrait of Emma Schmidt-Muller - 1915

No comments:

Post a Comment