While in my middle twenties,

I went to a party in an apartment building located in one of the better areas

of Manhattan

“But,” I replied, “most of

these artists received rigorous training in their craft and early on tackled

the conventions of representational imagery,

De Kooning, for instance, from a very early age was trained in

traditional techniques in his native Holland, eventually landing secure

employment producing commercial art.

I’ve seen a couple of his early representational pieces that would amaze

you.”

He was surprised and a

little doubtful, but, without a foundation in this area, had no choice but to

concede the point and let the discussion drop.

|

| Willem de Kooning - Bowl, Pitcher and Jug - 1921 |

I tell this story not to

poke fun at my friend. I am sure that at

some point in my development I shared his opinion and could make neither head

nor tail of abstract art. The effort to

convincingly translate form and space into a two-dimensional format is very

challenging and requires many years of training and experimentation to

master. It’s difficult when immersed in

the struggle to acquire the traditional techniques of creating representational

imagery to seriously consider work that seems to discard the very skills you

are trying to attain.

However, by the time I was

an undergraduate art student at SUNY Stony Brook, I was ready for some

experimentation. I approached

abstraction warily, without serious commitment on my part. Though abstraction begs for a large format, I

worked on very small canvases, unwilling to squander precious resources on a

flight of fancy. I really didn’t

understand what abstraction was about, how powerfully emotive it could be. Since at that time my figurative work was

about spontaneity and immediacy, I avoided nuance, working in pure tones

applied in impasto.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Abstraction I -1978c |

This work seeks to discard a

traditional approach to composition but fails, ultimately retreating to

comfortable conventions. Paint handling

is consistent, unvaried and uninteresting.

It really offers none of the technical, visual rewards that one would

expect from an abstract painting.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Abstraction II -1978c |

It’s difficult to abandon

subject matter when painting. Here I

suggest biomorphic forms without providing tangible definition. We might be peering into the lens of a microscope

to view strange, multicellular organisms.

The beings could be alien lifeforms, prehistoric creatures or

robots. Whatever is going on here, the

overall effect is whimsical. I was

definitely under the influence of Arshile Gorky and Joan Miró.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Backyard Abstraction - 1979 |

Of course, it was inevitable

that I would take the Jackson Pollock route at least once. There was a twenty year accumulation of

partially filled house paint cans in my parents’ basement. I popped open a few of them to create this

unsuccessful abstraction inspired by the view out the backdoor of my childhood

home.

I think that to paint a

successful abstraction it is essential that the artist has attained a true

understanding of and passion for paint itself.

Early on, paint, for me, was solely a vehicle to create an illusion of

space and form. There are so many things

to consider when painting (composition, perspective, anatomy, the opposition of

lights and darks, tonal value, color harmony, etc.) that it’s easy to lose

touch with the medium itself. Only when

technical concerns are addressed intuitively, almost unconsciously, after years

of persistent activity, does one begin to appreciate the medium itself: the

pull on the brush when applying paint to a still tacky lower layer; the way thinned

out paint splatters or drips when rapidly brushed onto a surface; how impasto

paint retains the imprint of the brush and documents the path and speed of the

stroke; how a thin glaze of color effects the tonal value of the layers below;

or what happens when a palette knife is raked over still wet paint. It took me years to learn that paint is subject matter.

Let me digress a moment to address

terminology. Probably one of the most

confusing words used to define a technical approach to creating imagery is

“abstraction”. When modern artists first

started to experiment with imagery not firmly rooted in reality, they began

with real subject matter which in their translations was distorted and

disguised to the point at which compositional concerns and emotional impact

became the determining factors on how that subject matter was represented. At times, the subject matter of the artwork

could still be easily recognized. At

other times, the subject matter was nearly obliterated. But regardless of how far the artist wanted

to push it, he was in effect “abstracting” from reality. For instance, Wassily Kandinsky codified or created symbols for the things that resonated most powerfully with him (horses,

cannons and mountains, for example).

Over time, the symbols became so abstract that they were barely

recognizable, but they continued to be necessary to the artist to initiate the

process of painting.

|

| Wassily Kandinsky - Composition IV - 1911 |

Eventually artists naturally

transitioned to creating work that had no link to any real visual reference,

but unfortunately the label “abstraction” stuck. To differentiate this new radical approach to

creating imagery from that of traditional abstraction, the term “pure

abstraction” was applied.

While experiencing a

particularly inventive period during my years in grad school, I thought myself

ready to tackle pure abstraction. My

appreciation and understanding of the properties of paint were probably at an

all-time high, and I was ready to seriously commit myself intellectually to the

process of painting without subject matter.

Part of that commitment was working in a larger format – much more

appropriate to the approach.

|

| Gerard Wickham - Abstract Painting - 1984 |

In this work, I explored

what could be achieved through limited means.

I confined myself, for the most part, to applying paint of fairly

regular consistency with a brush. I

restrained my brushwork and restricted my palette. My intention was to let the paint play the

lead role. Though this work is by no

means a masterpiece, I enjoy its overall effect of regularity occasionally

interrupted by accents of concentrated color, the way that the barely

perceptible tightening of the brushwork at the top of the canvas suggests space

and the aura of complacency implicit in its execution.

|

| Gerard Wickham - The Red X - 1983 |

By far my most successful

abstraction, The Red X was painted

using every technical means I had mastered during my years of study. It was first constructed by establishing a

subtle foundation of pale zones which was then overlaid with a network of bold

strokes (generally ranging from dark gray to black). The brushwork was varied and inventive – many

times amended or edited out completely by subsequent washes of pale

pastels. The green area in the lower

right of the canvas was painted for the most part in impasto, which in turn

demanded the counterbalance of the orange glaze above it. The composition functioned pretty simply:

weak vertical sectors of activity flanked the left and right-hand sides of the

canvas providing structure and stability while an overall diagonal provided

stress and movement. Sensing that the

painting was nearing completion, I stopped at this point to survey my work and

recognized that the right-hand side of the canvas was far more active than the

left. I placed a bold stroke of bright

red on the diagonal axis of the composition running perpendicular to the

diagonal’s thrust. It wasn’t enough, so

I pulled a line of paint away from that stroke somewhat toward the center of

the canvas. Later when I examined the

painting, I saw that the two strokes resembled an “X”, and when Sam Gelber

suggested that calling the work “The Red X” would be natural, the name stuck.

Without a doubt, a few

fledgling attempts at pure abstraction do not make one a master. Artists devoted many years, often the

entirety of their careers, to attaining a fluency in the technique. I never seriously considered pure abstraction

an avenue that would permit me to fully address my artistic concerns, either

intellectually or emotionally, though I enjoyed the challenge of the occasional

technical exercise. Even so, I learned

to appreciate and greatly respect pure abstraction, studied the work of some of

the giants in the field and avidly sought out exhibitions of their work.

I’ve

put together a small selection of artwork, that I particularly like, created by

a variety of painters who worked in a purely abstract manner.

New York School - Action Painters

|

| Willem de Kooning - Untitled - 1950 |

|

| Jackson Pollock - Autumn Rhythm, No 30 - 1950 |

|

| Franz Kline - Mahoning - 1956 |

New York School - Color Field Painters

|

| Mark Rothko - Orange, Red, Yellow - 1961 |

|

| Adolph Gottlieb - Flotsam at Noon (Imaginary Landscape) - 1952 |

School of Paris

|

| Wols - It's All Over The City - 1947 |

|

| Serge Poliakoff - Abstract Composition - 1954 |

|

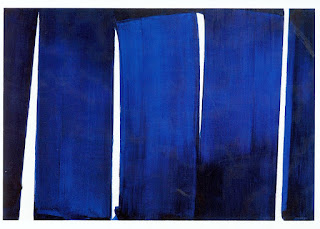

| Pierre Soulages - Bleu - 1972c |

Second Generation Abstract Expressionism

|

| Joan Mitchell - City Landscape - 1955 |

|

| Helen Frankenthaler - Into the West - 1977 |

Bay Area Abstraction

|

| Richard Diebenkorn - Ocean Park #79 - 1975 |

Various

|

| Mark Tobey - Universal Field - 1949 |

|

| Antoni Tapies - Painting - 1955 |

|

| Asger Jorn - Green Ballet - 1960 |

|

| Brice Marden - Cold Mountain Series, Zen Study 2 - 1991 |

|

| Gerhard Richter - Abstract Painting - 1987 |

All comments are welcome. If you prefer to comment privately, you can email me at gerardwickham@gmail.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment